The Issues 2024: LGBTQ Rights Are in Grave Danger

For the past few weeks, Literary Hub has been going beyond the memes for an in-depth look at the everyday issues affecting Americans as they head to the polls tomorrow. We’ve featured reading lists, essays, and interviews on important topics like income inequality, health care, gun culture, and more. For a better handle on the issues affecting you and your loved ones—regardless of who ends up president on November 6th (or 7th, or 8th, or whenever)—we have you covered. You can catch up on past features here: Income Inequality, The Importance of Labor, The High Costs of a For-Profit Healthcare System, The National Epidemic of Gun Violence, The Urgent Importance of Reproductive Rights, and The Fight for Climate Justice.

Today we’ve gathered the best stories published at Lit Hub about the grave risk to the basic human rights of millions of LGBTQ Americans.

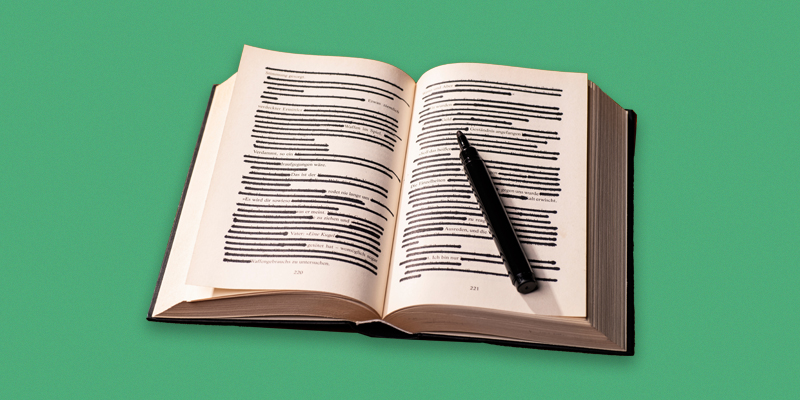

On the Clear and Present Threat of Book Bans: A Conversation with Librarian Jess deCourcy Hinds

Calvin Kasulke talks to librarian Jess deCourcy Hinds about banned books, libraries, and fighting back against attempts at oppression. BONUS RESOURCES: FReadom Fighters • Advice on writing to elected officials or your local newspaper • Advocate for School Libraries • Anti-Censorship Toolkit from Book Riot • Librarian Amanda Jones’s story of fighting back and suing her tormentors.

The 10 Best Formally Inventive Queer Memoirs

These ten books resist tidy categorization, because it is not quite right to call them “memoir” when at their center they are works of art and scholarship, philosophical treatises and critiques. They are representations of the body, of types of bodies, of lacunae; they are bridges crossing a river of the unsaid to the archive. They exist in self-reflexive dialogues, they use language as a tool for invention, not to parrot the familiar.

Even in its least violent forms, discrimination on the basis of gender or sexuality is a violence of erasure, of not seeing as a form of denying a person their authentic existence. Keenly aware of that empty space, these ten writers write into it, unafraid, to give us these books that tell of transness, motherhood, domestic abuse, AIDS, loss, art-making, funerals, fish, and most of all: love.

My Queer Life Is Not Inappropriate, and Neither Are the Books That Reflect It

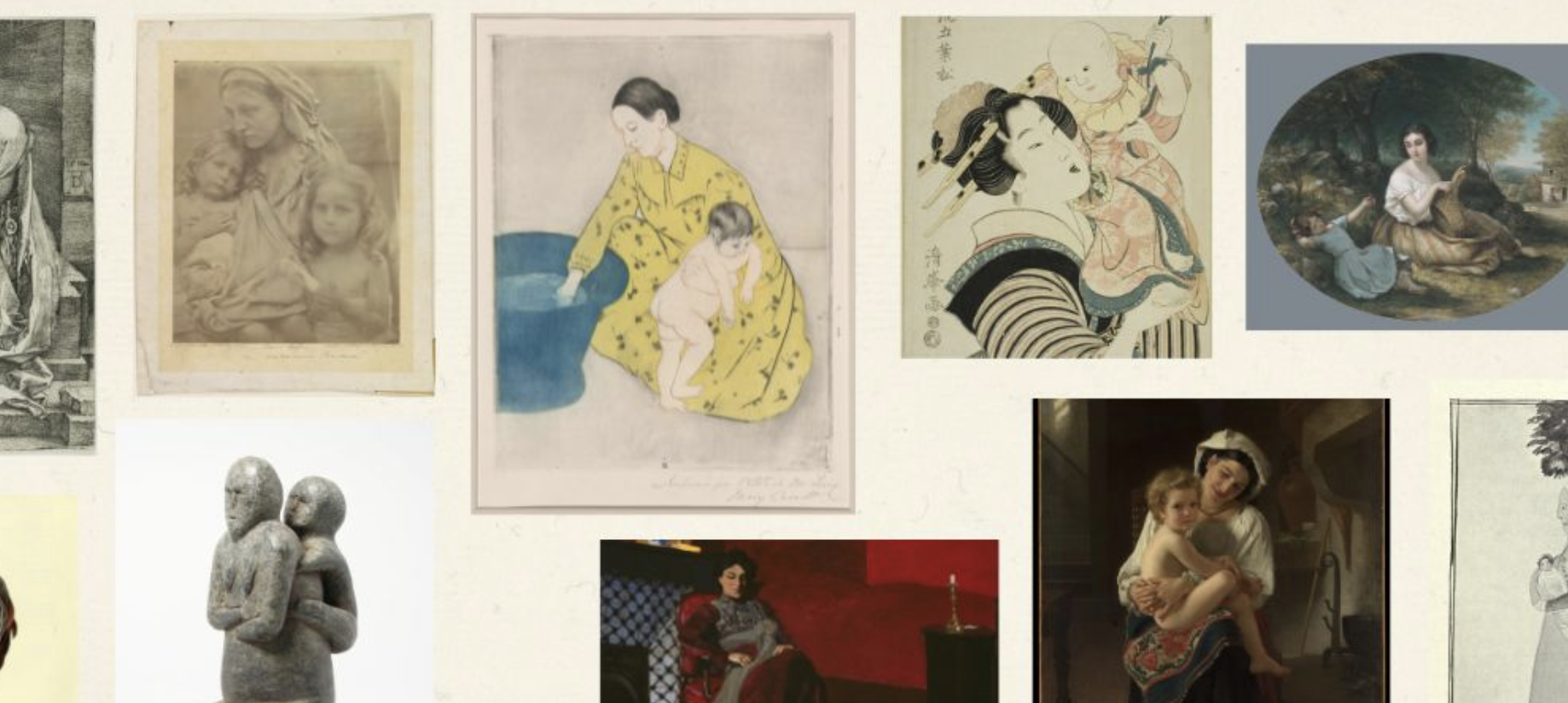

People are often taken by surprise when I tell them that I’ve always, as long as I can remember, wanted to be a mom. Maybe because by the time I realized I was queer, I was already in my twenties and hadn’t talked about how badly I wanted to have a family of my own someday, because I was too afraid of admitting what that family would look like.

Maybe because I hit a point where I didn’t believe I’d ever get to be a mom after all, so why should anyone else believe it was meant to be, either?

It took me a while to understand at all that I was queer. I went to a small Catholic school, and I was pretty sheltered inside of those white, straight, cisgender walls. I remember, very clearly, working on a group project in the seventh grade. A friend, Kristen, and I were sprawled out on the classroom carpet, cutting out pictures from a magazine to then paste onto a posterboard. While flipping through the magazine, I asked Kristen, “Do you ever just really, really like the way another girl’s face looks?” Of course she didn’t understand what I was saying. I didn’t even understand what I was saying, that what I was talking about was attraction.

The Purpose of Book Bans Is to Make Queer Kids Scared

I joke about it now: “Until you’ve seen a priest calling you a pedophile at a city council meeting…”

But when someone first sent me the video I couldn’t watch more than a few seconds of it. I thought I’d be fine. I’ve dealt with homophobia before; I’ve been called the f-word just for standing a certain way, even while growing up in NYC. This was just a school board meeting on the other side of the country. I thought, What do I care what these people think of me? I thought, “this is just going to be the same hateful stuff.”

What made me stop watching was the crowd around the priest as he said these things in his mannered, reasonable voice. The respect they afforded him. At a meeting where I wasn’t asked to speak, given no voice to defend myself. Others in the video defended queer books, arguing for how needed they are in school libraries, the value of the books I’ve written for teens. But I wasn’t there. My voice wasn’t heard. Instead, there was priest, in a collar, and with a calm voice. He accused me of a crime, and people nodded.

Books Have No Gender: On Being a Small Town Librarian While Raising a Trans Child

When our daughter was two—and still known as a boy—and I was a handful of years into my position at the library, the children’s room needed a new librarian and I needed more hours. It wasn’t a position anyone would have envisioned for me—I wasn’t animated and sociable, like all the previous children’s librarians, and I didn’t do crafts. But I cared deeply about literacy, and having a child meant I was learning a lot about children’s books. I moved downstairs, to the children’s room, where a woman named Lisa already worked. When she’d first moved to town from just outside New York City, she’d shocked me with her personality, which was so far from the reserved New England character I was accustomed to.

“We should go out sometime,” she’d said the day we met. “What do you like to do? We could go for a drink? Or dinner? Give me your phone number.”

Her nails were professionally manicured, her clothing bright. She was in high heels in the afternoon, and she had a large diamond on her finger. I was dumbfounded. “I really don’t go out,” I said pathetically.

Censorship Through Centuries: On the Long Fight for Queer Liberation

More than one hundred children and adults walked through metal detectors and past bomb-sniffing dogs to attend Drag Queen Story Hour at a community church in northeastern Ohio in December 2022. Drag Queen Story Hour began in San Francisco in 2015 as an effort to encourage literacy and provide children with queer role models. Libraries and bookstores across the United States began to host the story hours, some of which drew many times the usual number of people who typically came to library events. But protests against it also grew more frequent.

The Ohio church’s pastor, Jess Peacock, had fielded “accusations of pedophilia, grooming, and horrible things being done to kids” in the days leading up to the December 2022 story hour. Violent threats prompted her to spend $20,000 on security measures.

Just the day before the story hour, federal authorities arrested Aimenn D. Penny, a neo-Nazi, for attempting to “burn…the entire church to the ground” with Molotov cocktails. Penny told authorities that he had targeted the church “to protect children and stop the drag show event.” Penny belonged to “White Lives Matter, Ohio” and had distributed white nationalist literature.

111 Queer Books Recommended by Librarians, Booksellers, and Authors

While we celebrate queer literature and history all year long at Lit Hub dot com, we also love a good book list. This year, in honor of Pride, we reached out to some of our favorite librarians, booksellers, and authors and asked them about the queer books they find themselves recommending over and over again—the ones that no library would be complete without, book bans be damned. The resulting list of 111 books—categorized by classics, contemporary, nonfiction, poetry, YA, and children’s—is by no exhaustive (we’re not that good). But it is joyful, varied, and personal, the virtual equivalent of dropping into a bookstore and asking the coolest person what to read next.

“Endlessly Seductive, Endlessly Terrifying.” Lucy Sante on the Idea and Reality of Transition

Between February 28 and March 1, 2021, I sent the following text as an email attachment to around thirty people I considered my closest, most consistent, day‑to‑day friends. While I sent the emails out individually, the subject line was usually the same: “A bombshell.” I smirked at the unintentional pun and wondered whether anyone else would. It was simply titled “Lucy.”

The dam burst on February 16, when I uploaded Face‑App, for a laugh. I had tried the application a few years earlier, but something had gone wrong and it had returned a badly botched image. But I had a new phone, and I was curious. The gender‑swapping feature was the whole point for me, and the first picture I passed through it was the one I had tried before, taken for that occasion. This time it gave me a full‑face portrait of a Hudson Valley woman in midlife: strong, healthy, clean‑living. She also had lovely flowing chestnut hair and a very subtle makeup job. And her face was mine. No question about it—nose, mouth, eyes, brow, chin, barring a hint of enhancement here or there. She was me. When I saw her I felt something liquefy in the core of my body. I trembled from my shoulders to my crotch. I guessed that I had at last met my reckoning.

Moral Panics Never Go Out of Style: On the Corrosive Effects of the Culture Wars

Long before Donald Trump occupied the White House, small communities across the Pacific northwest became laboratories for populist campaigns that exploited people’s fears and turned neighbors against one another. I’ll never forget Penny, a white single mother who told me that she resented those who used food stamps to buy avocados. “I can’t afford avocados,” she lamented, “but they’re buying them like there’s no tomorrow.” Her resentments spilled over in different directions, directed toward immigrants, people of color, uppity city slickers, and anyone else who seemed, to her at least, to work less but have more than she and her family did.

Globalization and automation had shaken the region’s timber-based economy, reverberating in small, central Oregon communities like cottage Grove (which I called Timbertown), where Penny lived. She had lost her job as a nursing assistant, and when her unemployment benefits ran out, she had few other options.

Winning the Culture War Against Queer Kids’ Books

I was celebrating the release of my third middle grade novel, The Truth About Triangles, at a recent bookstore event when someone asked me, “How does it feels to write LGBTQ+ stories for young people?” I paused, overwhelmed by the tangle of words this question brought up. But one word stood out.

“Impossible,” I said. “It feels impossible.”

I didn’t mean that it’s impossible to write these stories. It’s the fact that I get to write them that blows my mind. You see, I grew up in a conservative, evangelical household in the Midwest that upheld bigoted beliefs about the LGBTQ+ community. I knew early on that I wasn’t straight, but I felt like I couldn’t say anything. I didn’t know how.

The Joys and Fears of Trans Motherhood

I’m no mother yet, of course. I’ll never really know what it’s like until I’m one. And my and my wife’s experiences as mums will ultimately be unique to us. But I already recognize this flowing uncertainty, this tidelike push and pull of the mother-child bond, from my relationship with my own mother—and, from that, the kind of mother I don’t want to be, especially in an America where queer, interracial families like mine are under threat from anti-queer, tacitly—or explicitly—white-supremacist conservative agendas.

An America where, so often, the flag that one citizen has pledged allegiance to has not, itself, pledged allegiance to another, as James Baldwin said in his famous debate against William F. Buckley—and what kind of citizen that flag will pledge allegiance to if the MAGA movement wins any future elections is a question I wish my future little one would never have to answer, but almost certainly will.