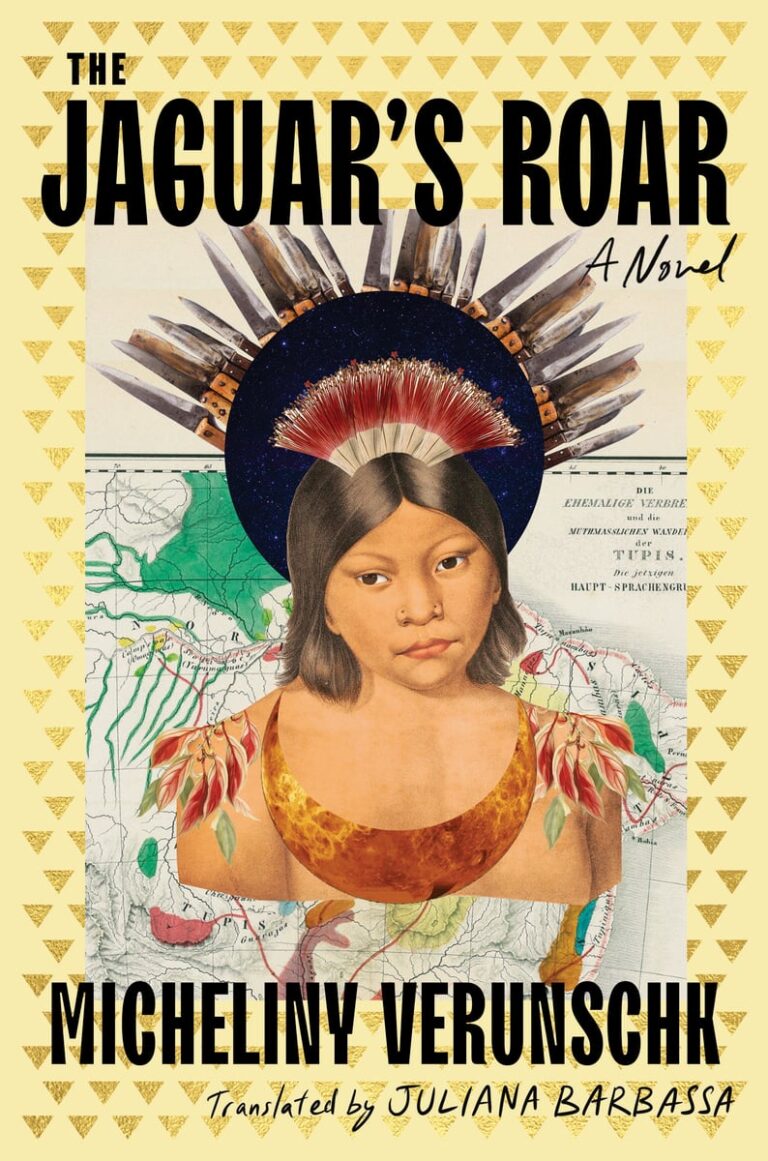

The Jaguar’s Roar

This is the story of Iñe-e’s death. It is also the story of how she lost her name and her home, and the story of how she remains vigilant. Of how she was taken across the sea to a land of enemies. And of how, through their arts, she lost and then recovered her voice. Listen: This voice that I am introducing to you here is not the voice that echoed in the forest, calling to her older brothers as she gathered fruit to take to the maloca. And it is certainly not the voice that was silenced beneath the storms and the captain’s cries, the voice stifled in shame over the mystifying imprecations of scientists, or suppressed by the tittering of courtiers and the brusque impatience of the Fraüleins.

This is also not the voice that was oblivious to what the newspapers and the magazines of the time said about her, or the letters in handwriting that meandered like tendrils on a vine. The voice you will perhaps hear in your head and that will mingle with your own voice, or the voice of your daughter, or of the child next door, or who knows, the voice of your grandmother, whoever she may be, is not the voice Iñe-e had when she was born. It is not the voice that turned to stone in her throat when she went to live in the great castle among people nearly translucent in their pallor, their flesh, soft and sour, moving under cloth that was dazzling and full of color, beautiful, but not enough to conceal their repugnance, their hair so often faded, without the luster imparted by the black dye of the huito fruit. It is also not the voice she secreted away, a treasure kept close, so her enemies could take no more from her.

This voice and this language, and even these letters, so well ordered, arranged neatly one after the other, ants beaded across the floor, have been lent to Iñe-e, this being the only means available. The most efficient. And though this language might be harsh, piercing, there is some freedom in how it may be used, acquired, as it was, at great cost.

So if there is a refusal to use the word taxidermy and the word disenchantment is chosen instead, it is done out of stubbornness. And rest assured that Iñe-e would approve. If, instead of river, she says muaai or even Fluss, take it as an admonishment of what was done to her. In telling this story, she warns, there is no room for forbearance. This language, this voice, is chosen for the pain it can deliver. It can be poisoned, as Miranha warriors poison their darts with curare made with the sweat and blood of the women. It can be set on fire, a hot and bitter curare. And in any case, as you know, it can be used at will.

This is the voice of the dead, the language of the dead, in the writing of the dead. All of it is riven with faults, true, but what can I do except tell this story through the cracks? Like a plant that breaks through the imperviousness of brick, its roots prowling the dark, the vigor of its leaves imposing a new landscape, this story reaches for the sun.

When Iñe-e died, she was twelve years old. This, then, is the voice of the dead girl. Should anyone hear in it a hoarse-ness and take it for an ancient voice rising from a frozen grave, I can vouchsafe that it is from childhood that this voice springs, sprouts, and grows. And a child’s voice, of course, is wild, feral; it emancipates the senses.

And now that’s taken care of, let’s start from the very beginning. From what’s been chosen as the very beginning. And though some might object, might say this story started with a king who, his satchel full of coins from a greedy bourgeoisie, decided to take to the sea, yes, the one, the Sea of Darkness, I say no, this story really started with Iñe-e.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Jaguar’s Roar: A Novel. Copyright © 2026 by Micheliny Verunschk. Translation copyright © 2026 by Juliana Barbassa. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.