The Utopian Practice of Cruising

I am currently sitting in the foyer of a hotel near the San Francisco airport. I’m hard at work writing my next book. I’m also, as the guy across from me notices just now, hard in that other sense of the word. I had hoped he’d notice. We’d been eyeing each other for a while. He’d gotten a drink at the nearby Starbucks and his imposing thighs, framed by delightfully short shorts, had first caught my attention, as had the white Nike Jordan essential tube socks that similarly hugged his well-sculpted calves. Novice that I am at cruising, I had worried the glances I kept catching from him were accidental. It’s why I’d moved my laptop off my lap and given him a better view of, well, my actual lap. And so, next time he looked toward me in a casual way that didn’t let the girl friends he was with notice his distraction, I found his gaze landing on my right hand, which rested (quite seductively, I assured myself) on my clearly aroused dick. I rubbed it a bit. He licked his lips. And then, as if following a tacit script we both knew by heart, he got up, excused himself, and headed toward the restrooms down the hall.

I didn’t—couldn’t, really—hesitate. And so, despite the fact that I’ve been struggling to crank out my desired daily word count this week, I pack up my laptop in a rush to catch up with him. Only, by the time I enter the hotel’s public restroom, he’s nowhere to be found. Damn, I think. I must have miscalculated his interest. Which is a pity because if his legs (and freshly shaved angular facial features) were any indication, he’d make for a delicious notch in my budding hook up history. And so I take my place in front of one of the urinals and make as good use of this writing break as I can. It’s then I see the door to one of the two stalls open; his smirk informs me he’s very pleased to see me, if slightly annoyed that someone else in the other stall will limit what we can get away with. Standing side by side in adjoining urinals, we eye each other’s cocks (he’s clean shaven all over, it turns out). Eventually he’s brave enough to reach his hand around and cop a feel—all before a slew of men walk in and break our makeshift intimacy. Outside the restroom he only spares himself enough time to tell me what was absolutely necessary. “Wait until I leave my friends. Then follow me upstairs: 4081.”

Research, I tell myself, often comes from the unlikeliest of places.

When I first started telling folks that my next project would be all about the transient intimacies we can build with strangers, about the way in which brief encounters could be sites of endless possibilities, winks and nudges and snickers ensued. Oh how interesting that research would be, I was told. Talk about fun field work, right? Friends enjoyed making me blush with such ribald ribbing. The truth was that at some point I would need to up my cruising game if I was to feel in any way prepared to engage intellectually with the ideas I was pursuing with this project. I’d need to put in hours in the field lest my musings on cruising feel more like a sterile book report than an embodied (and, yes, well-researched) meditation on the joys of this queer practice. How else would I find whether cruising, as writers as disparate as Leo Bersani, Garth Greenwell, Tim Dean, and Marcus McCann have expounded these past few decades, was (is!) a different way of looking, a queer mode of reading, an example of impersonal intimacies, proof of a new vision of sociability? Or, more to the point of this project of mine, how could I confirm if cruising was, indeed, a welcome template with which to reframe how we connect with strangers?

Following the instructions of the young hot boy in the Jordan socks I felt a novel thrill. I know, I know. “I’ve never done anything like this,” all but sounds like a pickup line. A classic, truly. But in this case, it was true. (Not that I told him so; few words were exchanged, in fact.) One of my boyfriends—the one who can successfully cruise a boy while out washing the car or on a 7-Eleven run—has long mocked me for my lack of experience in this matter. “It’s so easy,” he tells me often. “You just have to pay attention.” He was right, as it turns out. Following the many pieces of advice he’s given me over our many months together, I was able to connect with a guy in a public place with just eye contact and minimal body language and proceed to a second location with but a few words spoken in between. All I had to do was be open to what was around me. And to trust that I could make it happen, no matter how much of a novice I am in such situations. A novice in practice though definitely not in theory.

I first wrote about cruising in earnest for an undergraduate paper in an English class. Back in 2006 I was taking a course on gay literature and the syllabus included John Rechy’s 1977 novel, The Sexual Outlaw, whose subtitle doubles as an apt précis for its narrative project: “A Non-Fiction Account, with Commentaries, of Three Days and Nights in the Sexual Underground.” From its opening lines, which talk of “streets, parks, alleys, tunnels, garages, movie arcades, bathhouses, beaches, movie backrows, tree-sheltered avenues, late-night orgy rooms, dark yards,” and more, I was smitten. And intrigued. And mesmerized. And any number of other ways of describing what it feels like when a piece of writing cracks open the world for you. Rechy’s sexual underground was revelatory for a twenty-one-year-old college boy who was slowly trying to make sense of himself as an out gay man in a whole new country, and who understood that as mostly consisting of falling for boys who openly flirted with him and dreaming up future lives with them, in turn. Amid such sophomoric ideals about what gay life could offer, Rechy was a tempting proposition. After breaking up with my first ever college boyfriend I’d found a cute Aussie whose pop culture tastes neatly aligned with mine. And so, while I was reading about any and every filthy thing Rechy(’s protagonist) did in the streets of Los Angeles in the 1970s, I was blissfully living out a rather square (homo)sexual experience. I’d told myself Rechy’s “Jim” and his exploits on the page were an embalmed past I could never live out (hadn’t such cruising died out in the 80s and 90s with the closure of bathhouses, with endless park raids, and a health crisis that discouraged if not outright vilified such practices?), and so I approached The Sexual Outlaw as a kind of totemic text about an erotic fantasy as elusive and out of reach as any of the porn stories I used to read online in high school. When I first read it, I was bowled over. Never had a novel so turned me on while also intellectually stimulating me. I blushed at every other page, with shame, at times, but mostly out of a blissful kind of erotic and intellectual envy.

For cruising and hustling and scoring and “making it” in Rechy’s world wasn’t (solely) an excuse to drum up deliciously titillating scenes about fucking and fingering, about blow jobs and hand jobs, about orgies and one on one encounters. It was a cultural rallying cry. And, for a literary nerd with a penchant for queer theorization, the book proved to be a source of endless inspiration. Here was a way of apprehending so-called unsavory aspects of gay male culture in a productive way. Or so I told myself in the comfort of a classroom and the safety of a college discussion where I could entertain deliciously debaucherous scenarios that I didn’t dare live out in person. Out of fear, yes. And shame. And a distrust in my ability to dream up such possibilities. Rechy was the kind of gay man I aspired to be; his writing the kind I aspired to live in. In my twenties I could only think about cruising as an intellectual concept, one rife for interpretation and interpellation, one that served less as a guide for sexual pleasures out on the streets and more as a capable trope that helped me navigate what was happening on the sheets—on the pages, that is.

My brief fling with the flight attendant close to twenty years after reading about Rechy’s scandalous exploits felt like vindication. Sure, I’d been to bathhouses and to backrooms and secluded gay beaches and steamy dance floors. But this was novel. At last, and after years of thinking and writing about Rechy’s book, I had a cruising anecdote of my own—a textbook example of it, at that! All it required was a change in my own orientation toward the world. My boyfriend had insisted that all I had to do was pay attention. I had to be aware of my surroundings. Everywhere could be a cruising space if you were attentive enough. This is what Rechy teaches his readers. Not (solely) by showing us how public parks and restrooms (and alleyways and piers and the like) make fertile ground for sexual encounters but by embodying the openness required to invite and entice such interactions. That’s a lesson I’d learned from another book assigned to us in that gay lit class. William Beckwith, the protagonist of Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming Pool Library, doesn’t so much reveal London to be a vast endless space for “cottaging” (the Britishism for cruising) as much as he reveals himself as the kind of person that makes such a description of London feel self-evident. William scores aplenty everywhere he goes because he’s yet to meet a public space (or an attendant stranger) he couldn’t lustfully turn on.

Here lies the key to the cruiser: potential is everywhere if you so choose to seize it.

Cruising demands you reframe both how you gaze at the world but also how you invite the world’s gaze. William is able to cruise boys everywhere in London because there are no spaces where cruising is not the desired goal. Witness him describing the Tube: We’re told he found it “often sexy and strange, like a gigantic game of chance, in which one got jammed up against many queer kinds of person. Or it was a sort of Edward Burra scene, all hats and buttocks and seaside postcard lewdery. Whatever, one always had to try and see the potential in it.” Here lies the key to the cruiser: potential is everywhere if you so choose to seize it. Moreover, it requires understanding public spaces as rife for thoughts and actions that belong, we’re often told, in private. It’s why Hollinghurst cites Burra, whose early twentieth century portraits captured a lascivious vision of urban life wherein sensuality was always on display. Hollinghurst moves us to think of the London William observes as constantly being up for consumption, packaged for public viewing, postcards being the rare private correspondence that’s open to be read by anyone who chances upon it. William refuses to observe any distinction between different public or private spaces: “Consoling and yet absurd,” he muses later, “how the sexual imagination took such easy possession of the ungiving world.” Sex, in William and Hollinghurst’s worldview is—and could be had—everywhere. There is no fiction of such erotic intimacies as being corralled into the metaphorical “bedroom.”

Hollinghurst’s protagonist may well be a perfect embodiment, in all senses of the word, of the argument queer theorists Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner espouse in their famous 1998 essay, “Sex in Public.” Concerning themselves with how “heterosexual culture achieves much of its metacultural intelligibility through the ideologies and institutions of intimacy” (straight culture makes sex, for instance, something that only happens in the privacy of your own home between a socially sanctioned unit of two), their essay begins with a simple statement: “there is nothing more public than privacy.” In their North American context—and responding quite vociferously to the arguments put forth by conservatives like Jesse Helms—Berlant and Warner saw how intimacies have been continually privatized. The passing connections Hollinghurst’s William and Rechy’s Jim so relish are socially disdained, if not outright criminalized. Narratives of love and family end up indexing the only available forms with which we’re to be intimate with one another. Anything outside of that is marked, they argue, as other. As deviant. As criminal. But it’s in those “criminal intimacies” that Berlant and Warner see rife potential: “girlfriends, gal pals, fuckbuddies, tricks,” and the like are examples of close-knit relationships that are not easily legible within our socially sanctioned narratives (there are no “happily ever afters” in these stories, only, and even then just sporadically, “happy endings” at most). Queer culture, as they argue, “has learned not only how to sexualize these and other relations, but also to use them as a context for witnessing intense and personal affect while elaborating a public world of belonging and transformation. Making a queer world has required the development of kinds of intimacy that bear no necessary relation to domestic space, to kinship, to the couple form, to property, or to the nation.” Against the invective that the only kind of intimacy one should value is the one you nurture at home, in the bedroom, with one other person, Berlant and Warner reminded their readers that queer folks had been extolling the virtues of queer counterpublics and the tight-knit relations there created. In lesbian bars and gay tearooms, in cruising parks and public toilets, on piers and on the streets—even on phone sex lines and in soft-ball leagues!—there’s been no shortage of queer spaces where friendly, familial, erotic, and sexual relations have been championed. These are fleeting and fraught, mobile and transient as need be. But they are not for that any less important in helping to map out what, at times, feel like utopian visions of the kind of communities and relationships we could all be building.

William, who has but one close friend and barely puts any stock into his own familial relations, puts his energy in nurturing (however passing) intimacies with strangers. His London is rife with possibility precisely because he sees openings both literal and figurative wherever he goes. “There is always the question, which can only be answered by instinct,” William tells us, “of what to do about strangers. Leading my life the way I did, it was strangers who by their very strangeness quickened my pulse and made me feel I was alive—that and the irrational sense of absolute security that came from the conspiracy of sex with men I had never seen before and might never see again.” Those instincts, Will knows, are not infallible (a key scene in the novel occurs when, misjudging a possible score, he’s beaten to a pulp by a group of homophobic neo-Nazis). But those instincts nevertheless structure his view of the world. Cruising is, at its most utopian, an equalizing practice that squarely depends on expecting the best (the most, really!) from strangers. This is what Hollinghurst stresses all throughout The Swimming Pool Library: not for nothing does the inciting incident of the entire novel take place at a public restroom where William unexpectedly finds himself saving an older man’s life.

Cruising is, at its most utopian, an equalizing practice that depends on expecting the best from strangers.

Cruising has offered fertile ground for critics, thinkers, and scholars alike. As a practice long criminalized and often degraded from within and outside the community, cruising has, over the last few decades, emerged as a kind of utopian practice that requires us to dream up more generative modes of relating to the other, to the stranger. In Park Cruising, Marcus McCann notes that the “defining characteristic of cruising is its porousness. Cruisers show deliberate vulnerability toward strangers.” There’s no way to make yourself available to others if you’re closed off, something I’ve long been accused of being, or seeming (likely both). It’s why keying into such a mood comes with such difficulty for me. For McCann, such porousness opens up a different way of conceiving of our sociability: “I often think,” he writes, echoing the sentiment at the heart of Berlant and Warner’s work, “of the ways which non-monogamous and queer people build intimate relationships not just with one or two people but as a kind of fabric whose interwoven strands overlap.” The weaving metaphor is particularly helpful because it pushes back against the other image that’s often deployed when we think of our public interconnectedness with strangers: networking. McCann’s image is much more organic; it’s a more productive figure, too, with its own serviceable usefulness. But there’s also an expansiveness to it: you could make plenty of different things with any one fabric. Those queered intimate relationships can and could be endlessly refashioned, repurposed—recycled, even. McCann notes that we should see a phrase such as “the strangers in your life” not as an oxymoron but as a kind of koan. It’s an invitation to reassess why we so often feel compelled to revel in our estrangement from those we don’t (or will ourselves not to) know. There’s a tacit call toward empathy here, toward compassion. Filtered through lust, no doubt. But that makes the impulse no less ambitious. In his seminal treatise on cruising, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, Samuel R. Delany helpfully teases out the tenets on which McCann’s work is founded on. Delany understands the distinct aspect of cruising, as “contact” rather than as “networking.” This is why cruising is a concept inextricably linked with urban planning for Delany. Cruising is a practice that flourishes most acutely in densely populated areas where public spaces allow for such encounters to happen. The cruiser is an attentive observer of the urban world. And a rather active member of it as well. He moves through spaces with wide-eyed conviction that what he’s looking for is out there, ready and willing to be enjoyed. What could we gain, then, by being open and opening ourselves up to strangers this way?

What could we gain, then, by being open and opening ourselves up to strangers?

Such utopian considerations of cruising can leave one romanticizing the practice. Or a version of the practice. After all, nowadays, most queer folks encounter it mediated through screens where scrolling and filtering and blocking and ghosting have made it feel like an insidious way to know and covet others’ bodies. What’s lost in cruising for men on Grindr, say—or Sniffies, even—is the very contact with bodies Delany was so focused on. Such steamy tactility is lost when we’re reduced to squares on a screen, to headless torsos with a laundry list of wants and needs distilled on first look. This is perhaps why I reach back to the work of Rechy and Hollinghurst (and Jean Genet and Andre Gide, in turn) to better arm myself with how best to bring a cruising attitude into my everyday (and obviously my sex) life. There I find a call toward soaking up bodies and stares, gropes and glances, in ways that push back against the antiseptic way of approaching men with a neutered “Hey handsome” these apps so depend on and demand in turn. The very language of Rechy’s work, for instance, demands you relish the many encounters he chronicles; he pulls you closer (cruises you, say) into a world where bodies do plenty of communicating.

When we first read The Sexual Outlaw in class, we had long discussions about what Rechy and his fictionalized surrogate were seeking in their seemingly endless sexual conquests. What drove a hulking, muscled tan man in tight denim to scour the streets for one hook up after the other? Why did Rechy so chase after, on the streets and on the page, momentary connections that left him adrift, wondering out loud to his reader, whether any other kinds of bonds could be made between strangers in the night?

At every turn in The Sexual Outlaw, which notches hundreds of sexual encounters, Rechy seems to be running away from the possibility of being truly seen by another. “Jim” whisks himself away whenever he senses a closeness he wishes to expunge instead. For a character (and author) who so willingly gave his body away, those retreating gestures always struck me as indicative of something else; I even made the mistake of bringing it up once in class. “Don’t you think that Jim is just afraid of intimacy?” The thundering laughter that greeted my all too earnest inquiry haunts me to this day. So much so that the specifics of how our professor rerouted the conversation away from my question have melted away in the decades since. What was clear was that shame-filled mockery was the only way to neuter my insistence on Jim’s allergy toward intimate connections with his tricks.

Maybe what I was getting at was lost in translation, lost in the very language I am forced to use to make such questions legible. For Rechy’s various autobiographical avatars do seek out intimacy. Though not the kind we tend to value when we use such a word in everyday life. Jim shows no reticence to finding closeness in and with strangers. But it’s one devoid of the emotional vibrancy we call up when we think of intimacy within, say, a couple—married or otherwise. Perhaps my question, and the laughter it elicited in class, was indicative of the way this language fails us in understanding the myriad ways in which we can relate to strangers without falling back on known modes of relating to them. In Unlimited Intimacy, Tim Dean’s groundbreaking study on barebacking subcultures in the late 90s, he asks a better version of the question I was getting at in trying to figure out why Rechy’s Jim found closeness in distance throughout The Sexual Outlaw. It’s a question that pushes us to (re)imagine a different relationship with and to strangers. It invites us to relish the porousness with which we can approach and understand them. And more importantly, it asks us to rethink how and what we construe strangers to be. It’s a query that serves me, now, as the guiding principle of my cruising project, one that must be answered one score—one flight attendant with gorgeous calves—at a time:

“Why should strangers not be lovers and yet remain strangers?”

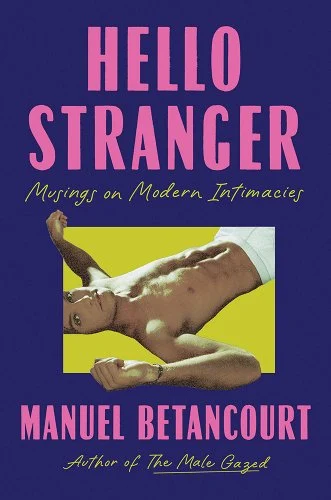

Copyright © 2025 by Manuel Betancourt. Excerpted from Hello Stranger. Reprinted by permission of Catapult.

The post The Utopian Practice of Cruising appeared first on Electric Literature.