The 11 Best Book Covers of October

Another month of books, another month of book covers. Looking at this list, all I can say is that October was weirdly beige… but in a good way? My favorites from spooky season are below.

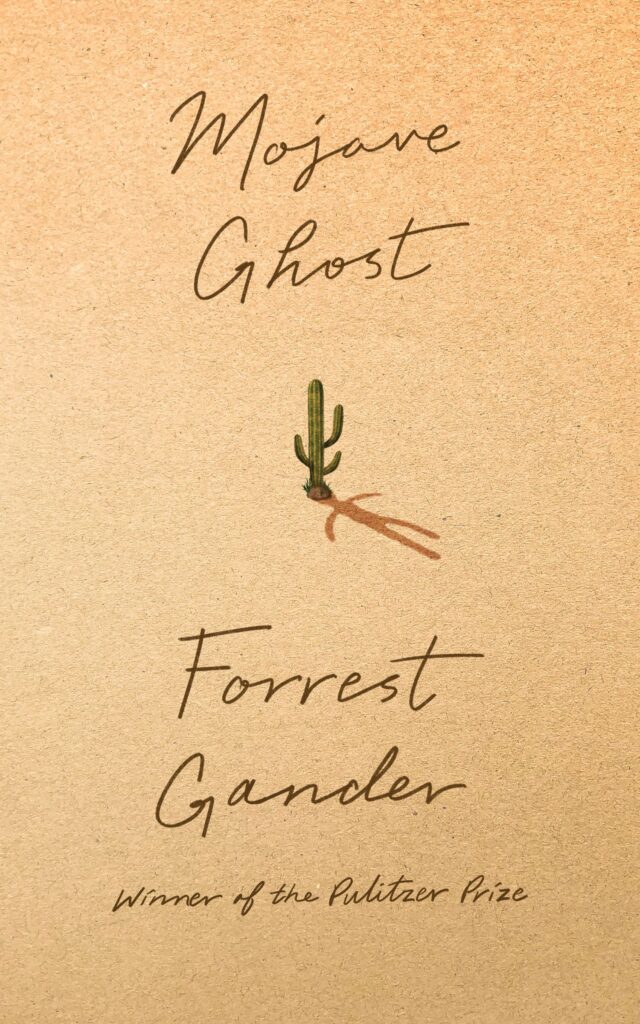

Forrest Gander, Mojave Ghost; cover design by Rodrigo Corral (New Directions, October 1)

Forrest Gander, Mojave Ghost; cover design by Rodrigo Corral (New Directions, October 1)

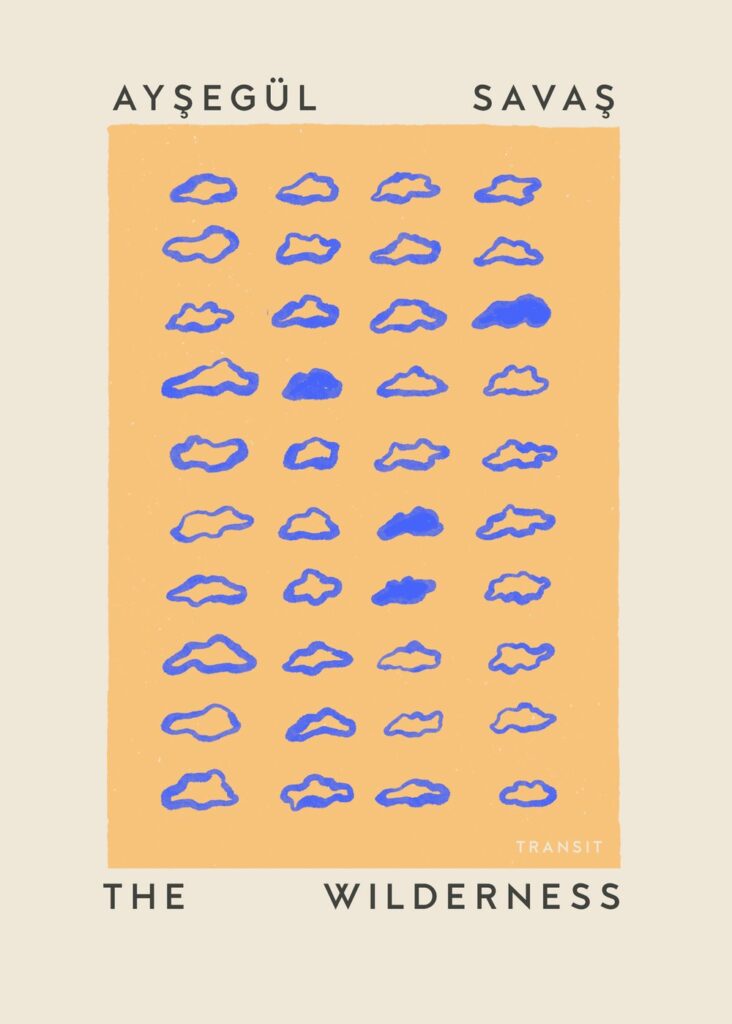

Ayşegül Savaş, The Wilderness; cover design by Anna Morrison (Transit Books, October 1)

Ayşegül Savaş, The Wilderness; cover design by Anna Morrison (Transit Books, October 1)

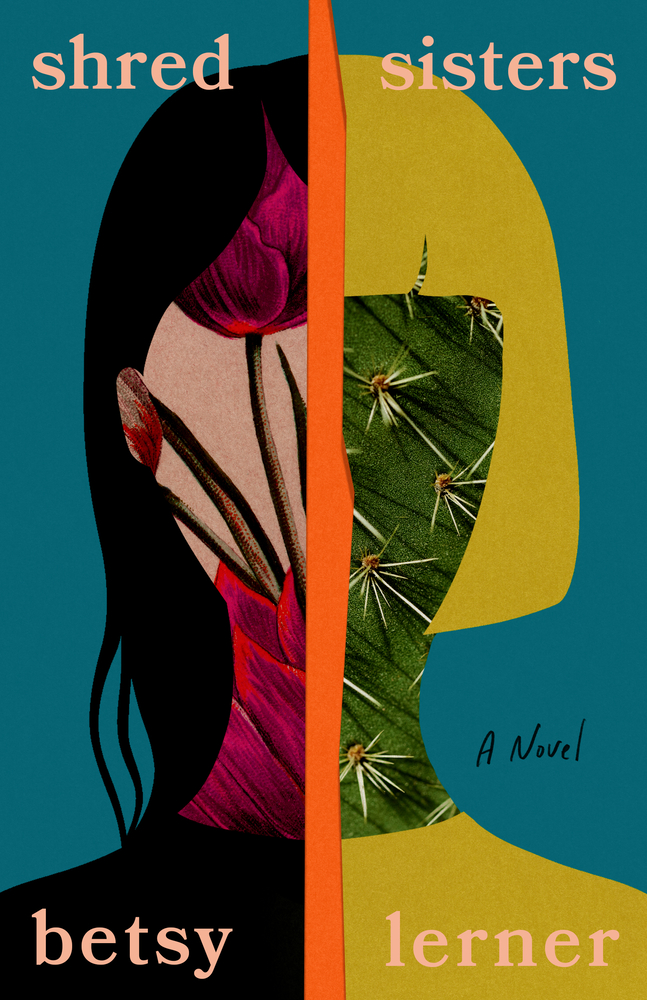

Betsy Lerner, Shred Sisters; cover design by Amanda Hudson/Faceout Studio (Grove Press, October 1)

Betsy Lerner, Shred Sisters; cover design by Amanda Hudson/Faceout Studio (Grove Press, October 1)

Witold Rybczynski, The Driving Machine: A Design History of the Car; cover design by Jared Bartman (Norton, October 8)

Witold Rybczynski, The Driving Machine: A Design History of the Car; cover design by Jared Bartman (Norton, October 8)

Rodrigo Fresán, tr. Will Vanderhyden, Melvill; cover design by Daniel Beneworth-Gray, cover concept by Daniel Fresán (Open Letter, October 8)

Rodrigo Fresán, tr. Will Vanderhyden, Melvill; cover design by Daniel Beneworth-Gray, cover concept by Daniel Fresán (Open Letter, October 8)

Mark Haber, Lesser Ruins; cover design by Kyle Hunter (Coffee House Press, October 8)

Mark Haber, Lesser Ruins; cover design by Kyle Hunter (Coffee House Press, October 8)

Johannes Anyuru, tr. Nichola Smalley, Ixelles; cover design by Jonathan Pelham (Two Lines Press, October 8)

Johannes Anyuru, tr. Nichola Smalley, Ixelles; cover design by Jonathan Pelham (Two Lines Press, October 8)

Susan Minot, Don’t be a Stranger; cover design by Janet Hansen (Knopf, October 15)

Susan Minot, Don’t be a Stranger; cover design by Janet Hansen (Knopf, October 15)

Lucy Ives, An Image of My Name Enters America; cover design by Kapo Ng (Graywolf, October 15)

Lucy Ives, An Image of My Name Enters America; cover design by Kapo Ng (Graywolf, October 15)

Christian Kracht, tr. Daniel Bowles, Eurotrash; cover design by Jason Heuer (Liveright, October 22)

Christian Kracht, tr. Daniel Bowles, Eurotrash; cover design by Jason Heuer (Liveright, October 22)

Cho Nam-Joo, tr. Jamie Chang, Miss Kim Knows and Other Stories; cover design by Ingsu Liu, illustrations by Mariko Enomoto (Liveright, October 29)

Cho Nam-Joo, tr. Jamie Chang, Miss Kim Knows and Other Stories; cover design by Ingsu Liu, illustrations by Mariko Enomoto (Liveright, October 29)