Torrey Peters Wants You to Write What You’re Ashamed of

Reading Stag Dance three times in a row was not just an indulgence—it was a necessity. Torrey Peters’ masterful exploration of gender gripped me from the first page. To say I loved this book would be an understatement. What I found within its pages was possibility. What brought me back every time was the raw, unfiltered intimacy that felt both deeply personal and universally resonant.

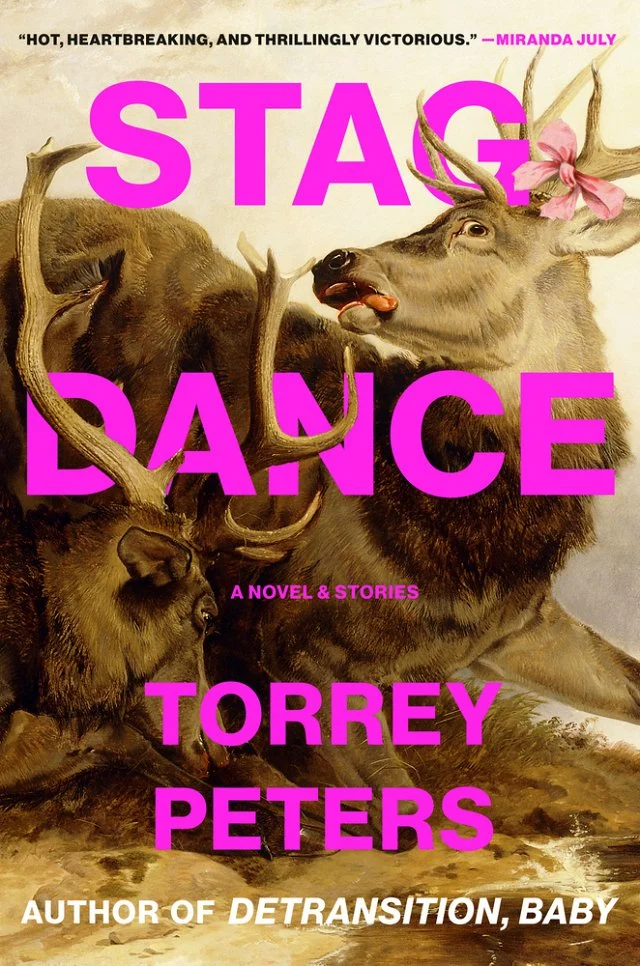

Stag Dance is composed of three short stories and a novella: an apocalyptic vision where a virus—unleashed by a group of trans women—reshapes the world; a teenage bro at a Quaker school struggles to accept his love for a sissy; a “Masker” crashes a trans women’s meeting in Las Vegas. Finally, a western telltale novella to end all western telltale novellas follows a lumberjack working for illegal timber in the depths of winter and grappling with his femmeness and his relationship to his fellow men.

What Peters accomplishes so brilliantly is cracking open the feelings of gender—feelings that not only belong to trans people, but to everyone who wrestles with identity, shame, and belonging. Stag Dance embraces the grotesque, the cruel, the darkly humorous, and the deeply human aspects of feeling gender and the ways it shows up in our relationships. Each story in this collection sizzles with emotion, pushing the boundaries of what it means to feel, to desire, and to exist, opening new ways to understand ourselves and each other.

This book arrives at a time of escalating persecution of trans people, amid a political climate steeped in fear, anger, and paranoia. Within its pages is something urgent and necessary—something that demands to be read, considered, and felt.

Julián Delgado Lopera: It’s incredible that Stag Dance is coming out as this new fascist coup is enacted and all these anti-trans orders are happening. It’s very timely and so good. Why do I love this book so much? First it deals with transness and gender expansiveness in a way that feels very refreshing. Very unapologetic. A command on a special intimacy around gender that is not trying to be didactic or explicate itself. How did you arrive at this very different lens around gender?

Torrey Peters: The binary that I’m interested in breaking with this book isn’t male and female, it’s more cis/trans. I think it’s easy for cis people to read about trans people and say, oh that’s so different than me, I can’t never understand. But in this book there’s only maybe three characters who identify with the word “trans.” Everybody else is just feeling a way. The thing that trans people feel isn’t unique to trans people, trans people have just named themselves trans. But cis people also have some of these feelings about gender, also have questions about sexuality, also are titillated. Cis people are constantly making a choice to have a gender. I wanted to shift Stag Dance away from an identity-based work to: let’s talk about how this stuff feels. Oftentimes being trans is about dwelling in feelings and trying to find names for those. Which is something we all do.

JDL: I absolutely love that. How did you come up with each story?

TP: The first stories were “The Masker” and “Infect Your Friends and Love Ones,” which are a horror story and a speculative fiction dystopia. I self-published them in Brooklyn around 2016 in a project I ran where I self-published novellas with other trans women. “Infect Your Friends and Love Ones” had to do with my relationship to the larger trans community.

Cis people are constantly making a choice to have a gender.

“The Masker” was about fetish—the fact that if you get to transness through fetish or sexuality, it is often considered not respectable, and also that there is some big difference between cross-dressers, transvestites, trans women [where] one is legitimate, one is not legitimate. Spoiler: in “The Masker,” there’s a character that wears a silicone full body suit, and what the book uncomfortably says is: maybe this person is also trans, even though all the other people in the story, including the cross-dressers, want this person to not be considered legitimate or trans. My third book was going to be a soap opera, but it turned into Detransition, Baby, so I returned to it later with the telltale western that is “Stag Dance.” And a teen romance, which is “The Chaser.”

JDL: As a person who has been many different genders, this examination of feelings around gender is one of the main elements that pulled me in. One of those feelings is shame. The main characters experience a lot of shame: shame in being close to someone that doesn’t pass fully, shame in loving and being attracted to a feminine boy; shame around desiring femininity and shame for another trans woman’s sense of womanhood. Could you talk about the role of shame in the book?

TP: Shame is intimately connected to fear. For example, when the pretty protagonist in “Infect your Friends and Love Ones” is walking with another trans woman and feels she is more likely to get clocked, that is fear. The actual threat is outside, but then the shame becomes, what if I am recognized as this person? What if this other person I will be recognized as is gross? And that comes back to, what if I am actually gross? Shame oftentimes is very revealing of where fear comes from and where it circulates in a person. When you write what you are ashamed of, suddenly the shame can be looked at. All of those thought processes that are normally recursive and hide themselves can be seen. It has a strange feeling of dissipating it.

I was ashamed when I was writing “The Masker.” I thought, everyone is going to think this book is disgusting, and not even because that much disgusting stuff happens, but just because I am ashamed of characters like The Masker who is a freak fetishist. I am ashamed of the older trans woman in that same story who thinks she knows what femininity is, but it’s an embarrassing form to me; I am ashamed of the sissy who is getting off on it. I wrote the entire thing in shame, and when I published it, I found solidarity. People read it and were like: I am like that, I see that, I feel that way. And instead of shame, I had the opposite: love and a group of enthusiastic people. It was a very powerful experience for me.

In my early writing about trans stuff, prior to “The Masker,” I really wanted people to like me. I wanted people to think I was normal. I wrote stuff that told people, don’t worry I’m totally fine, yes sure I dress up on weekends, that’s cool, it’s like some people go to football games and some of us dress up. I’m just like you. I’m in heels, that’s all. Not only was it dishonest but it reinforced feelings of shame I had, whereas writing into the shame was really freeing.

JDL: There’s a lot of cruelty happening, which I love. There’s a specific flavor of cruelty in the book, some arises from the shame, and sometimes it’s campy and dark. Robbie from “The Chaser,” for instance, is very cruel in a way that I found complex and fascinating, because technically the narrator, the bro, is the oppressor towards Robbie. But then that power shifts in the story, and Robbie ends up enacting many acts of cruelty on the bro that are only visible to the reader.

When you write what you are ashamed of, suddenly the shame can be looked at.

TP: I also love cruelty, it has always been part of my sensibility. And not only do I love cruelty amongst the characters, I also love cruelty towards the reader. A lot of [my] favorite books are cruel to the reader. Someone like Nabokov is incredibly cruel to his readers. Oh you liked this character? Let me do an awful thing. Cruelty is a kind of sublime embrace of the sticky gore of life, a way into the viscera of life. Love can get you there too, but it’s really just one side of it.

JDL: In most of the stories there is a flavor of cruelty that stems from queer intimacy. There is this sense of understanding each other really well, a depth of intimacy and knowledge that you, as the writer, are cracking open raw and using for cruel purposes.

TP: That’s very well said and observed. In order to be really cruel to somebody, you have to know them, they have to trust you. There’s betrayal in cruelty. Otherwise it’s just brutality. You’re right, cruelty happens with people who are intimate with each other, who know each other and who know the soft, painful places to press.

JDL: I want to move to “Stag Dance,” the novella in the collection. The voice of Babe, the main character, is very different from the other voices in the book and is so specific to a place, a particular kind of man, a specific social class. Some of his emotional expressions, for instance, I would re-read two or three times because they were so brilliantly articulated. How did you build this voice?

TP: There are two things to The Babe’s voice: the cadence and the vocabulary. Last winter, I wrote a page in that voice. It didn’t have any of the weird vocabulary, it was a voice that was trying to figure itself out, and it had a very strange cadence to it. A tumbling kind of cadence. I knew it was going to be a lumberjack because I was building a sauna in rural Vermont, and I was in the woods all the time. Gender-wise I was going nuts in the woods. I was alone building something, feeling independent, and because I grew up as a boy in the Midwest, it was like, if I’d never transitioned, I would be a lonely man in the woods building some shack on my own, telling myself that I am self-sufficient. So wtf did I transition for? Sort of like: if you change gender in the woods and there’s no one around to see it, do you even change gender?

I came to Colombia with those preoccupations and started researching. I found this book of lumberjack lingo from the turn of the century, a dictionary compiled [by] the sons of loggers in the 1940s. I started using the cadence and the words from this book. I wrote the first three chapters in really official logger words, and then about halfway through the book I started occasionally inventing my words. Like, whatever, Melville did it…I was reading Moby Dick and Blood Meridian, these classics of Americanah, and I’m writing in that genre. These cowboys and whalers are using obscure words from the King James Bible. It’s the discrepancies in the words that make books like Blood Meridian so interesting.

JDL: I was very interested in the moment when The Babe starts embracing his femininity and wearing the brown fabric triangle that’s supposed to be worn by any lumberjack who wanted to be courted as a lady. Just wearing this piece of fabric activated big changes in him. Talk a bit about that shift in the behavior.

There’s betrayal in cruelty. Otherwise it’s just brutality.

TP: I was thinking about prosthesis and the ways trans people, and cis people too, use prosthesis. For instance, when I have acrylic nails, they change the way I open my purse. I can’t just grab my purse with my whole hand, I have to daintily open it, and that creates a sort of feedback loop where then if I’m opening my purse so daintily, I better be dainty. For the Babe, instead of heels or nails or a strap-on or packing, his awareness of this brown fabric triangle pinned to his crotch is enough to reanimate his body. Something that happens often when you are trans—and sometimes for people who aren’t—objects become part of you. Your body is not actually contained. I sleep with people who use strap-ons and some sort of sublime thing happens where that is part of their body. The magic of it is not in the symbol of the phallus, it’s something different, something that we can imbue and extend our bodies outward into the world. For me, there’s something very special about this big logger taking this little piece of fabric and being like: I’m going to put all my femininity in it and animate it and bring it to life as part of me. It’s sad and funny and sublime and triumphant.

JDL: A sort of dystopian, dark, very alive nature is the backdrop of a lot of the stories. And in a way that feels very trans to me: ever changing and unexpected. It feels like nature is itself another character to which the main characters react. How did that come about?

TP: In this book I was more interested in: when I’m building the sauna and I’m alone in the woods and nobody sees me, how do I know I’m a girl? Much of the trans work that I have read takes place in urban settings where the background is a human-built world. My actual experience has been, for instance, intentional communities in Tennessee or out in Seattle where people are getting land, or trans motorcycle groups that are going places. The relationship between the material world, the natural world, can feel very different in the woods. I talked to a lot of Vermont women about this. How do I know I have femininity when every day I wear muck boots and Carhartt’s and go dig my car out of the mud? How do I show the occasional man what I want him to see? That spins out to all this weird nature stuff, in which the woods turns into a witchy place. This is where the supernatural stuff in the stories come from. My connection to this stuff is not gender theory but woods-witch feminine energy.

JDL: Is there anything I didn’t ask you want to share?

TP: When I published Detransition, Baby one of the things I got frustrated with was always being held up as representative of trans experience. In a funny way, Stag Dance is much weirder, and because of the political climate, I actually do want to speak out more. I hope to use its weirdness, make people think of trans issues more broadly. Not that I want to represent people, but I want to talk about things like solidarity this time around in a way that I didn’t the first time.

I would like to end by asking you something. We’re in a place of fear because of this rise of fascism. Is there an action around trans solidarity that people can take and/or a mutual aid org that you like?

JDL: For an action: call your trans elders. Take them out to dinner. It’s very important to focus on trans youth, but we cannot forget our elders. For organizations, there’s Fight to Live in NYC, which is a community effort working to end the incarceration of Black, Indigenous, and/or people of color who are queer, trans, and/or Two-Spirit in NY. And there’s El/La Para Translatinas in San Francisco.

The post Torrey Peters Wants You to Write What You’re Ashamed of appeared first on Electric Literature.