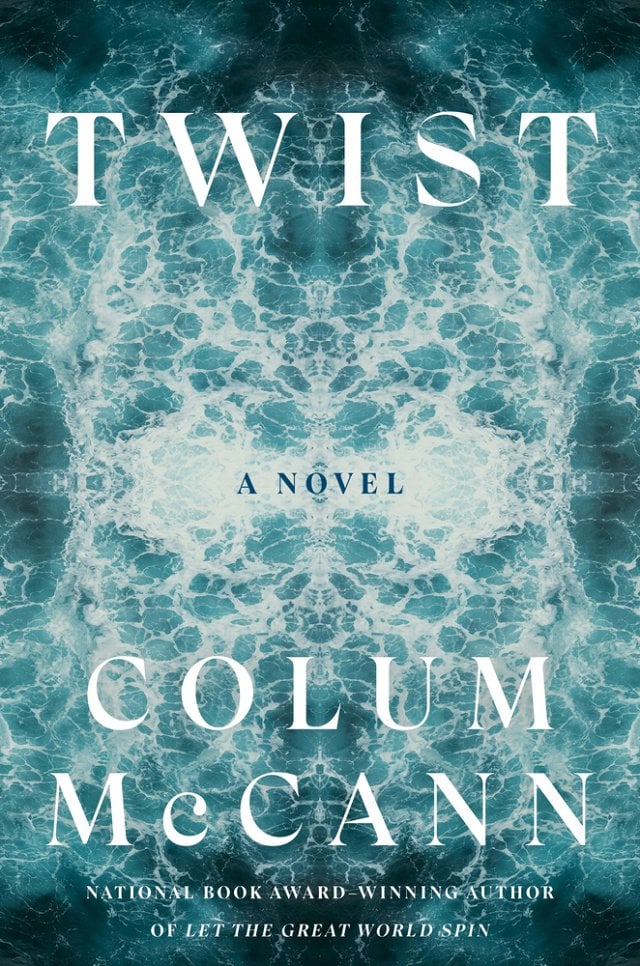

Twist

We are all shards in the smash-up.

Our lives, even the unruptured ones, bounce around on the seafloor. For a while we might brush tenderly against one another, but eventually, and inevitably, we collide and splinter.

I am not here to make an elegy for John A. Conway, or to create a praise song for how he spent his days—we have all had our difficulties with the shape of the truth, and I am not going to claim myself as any exception. But others have tried to tell Conway’s story and, so far as I know, they got it largely wrong. For the most part, he moved quietly and without much fuss, but his was a lantern heart full of petrol, and when a match was put to it, it flared.

I am quite sure that I will hear the name of Conway again and again in the years to come: what happened to him, what strange forces worked upon him, how he was wrecked in the pursuit of love, how he fooled himself into believing that he was something he was not, how we fooled ourselves in return, and how he kept spiraling inward and downward. Then again, maybe Conway was just being honest to the times, interpreting the present in light of the past, and perhaps he got it correct in some way.

I am not sure that anybody, anywhere, is truly aware of what lay at the core of Conway and the era he, and we, lived through—it was a time of enormous greed and foolish longing and, in the end, unfathomable isolation.

When all is said and done, the websites and platforms and rumor mills will create paywalls out of the piles of shredded facts, and we will piece together whatever sort of Conway we can to suit ourselves. Still, I’d at least like to try to tell a small part of his story, alongside my own, and alongside Zanele’s too, and if I take liberties with the gaps, then so be it. Like so many people nowadays, I’d prefer to sweep the memory of those days under the carpet. That I have made my mistakes is hardly unique. Maybe I tell this story to get rid of it, or to open up the silence, or to salve my own conscience, or perhaps I tell it because I am scared of what I too have become, steeped in regret and saudade. I often lie awake wondering what might have been if I had done things just a little differently. The past is retrievable, yes, but it most certainly cannot be changed.

*

In January 2019 I boarded the Georges Lecointe, a cable repair vessel. For a struggling novelist and occasional playwright, it was a relief to step away from the burden of invention onto a ship that would take me out to the west coast of Africa, a place I’d never been before. The center of the world was slipping, my career felt stagnant, and frankly, at my age, I was unsure what fiction or drama could do anymore.

I thought I would spend a few weeks on the ship, then return to Dublin and write a long-form journalistic piece, shake out the cobwebs. My first two novels had been minor successes, and I had written a couple of plays, but in recent years I had fallen into a clean, plain silence. The days had piled into weeks and the weeks had piled into months. Not much sang to me: no characters, no plotlines. The world did not beckon, nor did it greatly reward. As a cure, I had thought that I would try to write a simple love story for the stage, but it turned out to be a soliloquy of solitude, not a love story at all. I shut the laptop one morning. All my characters slipped into a chasm. I cast around for new ideas, but mostly it was fall and echo, echo and fall.

Everything felt out of season. I was drinking heavily, breaking covenants, refusing my obligations to the page. I bought myself an antique typewriter in an attempt to get back to basics, but the keys stuck and the carriage return broke.

So many of my days had been a haze. In my most recent novel I had been treading memory: the farmhouse, a small red light from the Sacred Heart, my father rising early to tend the farm, my mother trapped by shadows on the landing, my rural upbringing, my escape to London, the sunsets over the Thames, the journey home, the descent into suburban Dublin where the streetlamps flickered.

Some of the novel had been autobiographical, but the fictional elements were truer. All the truth, my father told me, but none of the honesty. I recall him stepping rather apologetically from the Galway theater where the book was launched. Rain on the cobblestones. Exit ghost.

I had a feeling that I had exhausted myself and that if I was ever going to write again, I would have to get out into the world. What I needed was a story about connection, about grace, about repair.

*

I had no interest in cables. Not in the beginning, in any case. In the one article I eventually wrote, I said that a cable was a cable until it was broken, and then, like the rest of us, it became something else.

Sachini, my editor at an online magazine where I did occasional work, called me one cold autumn afternoon. She spoke in long, looping sentences. She had happened upon a news report of a cable break in Vietnam and had been surprised to learn that nearly all the world’s intercontinental information was carried in fragile tubes on the seafloor. Most of us thought that the cloud was in the air, she said, but satellites accounted for only a trickle of internet traffic. The muddy wires at the bottom of the sea were faster, cheaper, and infinitely more effective than anything up there in the sky. On occasion the tubes broke, and there was a small fleet of ships in various ports around the world charged with repair, often spending months at sea. Was I interested, she asked, in exploring the story?

It was fascinating to think that an email or a photograph or a film could travel at near the speed of light in the watery darkness, and that the tubes sometimes had to be fixed, but my sense of the technology was limited, and it was all still a perplexing series of ones and zeros for me. I demurred.

Flattery has a double edge. I was not sure if I should be offended when Sachini called me the following week and insisted that I was one of the few writers capable of getting to the murky underdepths. She told me that, in some of her ongoing excavations, she had found a ship, the Georges Lecointe, that was purported to be among the busiest cable repair vessels in the world. It held the record for the number of deep-sea jobs in the Atlantic Ocean. She reminded me that I had specifically said that I was interested in the idea of repair. Tikkun olam, she called it, a concept I was not familiar with at the time. But repair was certainly what I craved. She also corralled me with the simple fact that the boat had been called in to help recover the black box of Air India Flight 182, destroyed by a bomb off the southwest coast of Ireland in 1985. More than three hundred people were killed and most of the bodies were never recovered. I had been fourteen years old at the time of the bombing, and I recall a photograph of an Irish policeman carrying a child’s doll through the airport. It intrigued me to think that a small black box stuffed with statistics and information could be hauled from the bottom of the ocean, but the bodies could not.

I walked along the Dublin coast. So much of my recent life had been lived between the lines. All the caution tape. All the average griefs. All the rusty desires. I had been an athlete once, a middle-distance runner. I had taken risks. Gone distances. Now I watched those in swimming togs who actually braved the cold water, and I envied them their courage. The sea tightened my eyes. For how long had I been walking around in the same set of clothes? I called Sachini. She hardly buoyed me when she said that a stint at sea might freshen me up, but she salved my mood with a decent word count and a generous budget.

I began my descent into the very tubes I wanted to portray. The owner of the Georges Lecointe was a telecommunications company in Brussels. The press department told me they were open to a visit from a journalist working in the international sphere. This, in retrospect, was quite naïve on their part, but they had languished publicity-wise in recent years, and they were engaged in several cable-laying bids with Facebook and Google—both of which were due to lay huge cables in the seas around Africa—and possibly thought that an article might raise their profile. It turned out that they owned a number of the world’s working cables: their insignia was a purple globe wrapped in spinning coils of wire.

I sublet my flat in Glasnevin, put my furniture in storage, and caught a plane to Cape Town, where the Georges Lecointe was docked. I arrived in the first week of the new year. I had decided to take a few days to acclimate. My only fear was that there would be a cable break and I might miss my chance if the boat was called out to sea, but the publicity team had assured me that they would alert me in the event of any news. I found myself a hotel where I thought I might unwind for a couple of days. Some sardonic copywriter had quoted Oscar Wilde in the hotel’s brochure: Those whom the gods love grow young. Such sweet irony. It was the weekend of my forty-eighth birthday.

*

After apartheid, I had thought Cape Town might be ashamed of itself, in the choke hold of history, riven still by all it had seen and heard and done. Maybe it was, but it hid that side well, or maybe I hid myself from it. There was a nod to the past just about everywhere—statues of Nelson Mandela, Miriam Makeba songs blasted out over intercoms, memory museums, rows of colorful banners—but apartheid’s successor was quite obviously itself. The city’s beauty stung my lungs, but its adjacent poverty pierced me too. I had beefed up on South African history and was willing to pour my own sorrows into the ears of the trees—Ireland, our famine, the Troubles—but instead I felt altogether, and a little uncomfortably, at home.

My boutique hotel lay jauntily at the far end of Gordon’s Bay. I wore an old T-shirt and torn jeans and walked among the junkies and the backpackers. These were essentially the people from my early twenties, and they reminded me that I had no need to return to my old self. The sea dragged its platter of pebbles to shore. Seagulls careened overhead, dropping shells on the rocks below, splitting them open. In the early morning, the fog came in fast around the mountain and struck a tuning fork in my chest.

I hired a car for a couple of days and drove the coast. The extraordinary wealth of the houses took my breath away. Their long green lawns lay out like rugs. Security booths manned the entrances: it was difficult to see any faces. It was as if nobody existed there at all. Everywhere seemed fenced. Signs for fences. Advertisements for fences. Fences within the fences. The only moving people were gardeners and joggers who quickly disappeared amid the trees and the wires. How had these people locked themselves off for so many years?

At the edge of a wealthy neighborhood, I saw a city dumpster actually rolling by itself down a steep street, set in motion by nothing I could identify, not even a dog or a cat. It started to move in a series of strange loops, clanging along, almost politely avoiding all the parked cars. It bashed off the pavement, hesitated a moment, then tipped over and leaked out a little of its refuse. A gull swooped and pecked at the leavings.

I had no idea that the poverty would sit at such terrible proximity. I turned off the road and there were the disheveled shacks, the potholes, the cracked water pipes, the ghosts wandering along the highways. Men and women pushed shopping trolleys stacked high with whatever little they possessed. The clouds sped away from them. Even the sky seemed segregated.

There were tours of the townships, and the pamphlets advertised them as ethical, but I couldn’t bring myself to return. I didn’t want to be the inconsolable European, walking around in exchange for an ounce of sentiment. I had heard stories of people shot for their dreadlocks. My voyeurism was not going to help. I had to turn around and face myself. Later, when Zanele wrote about the Joe Slovo township in Port Elizabeth, I marveled at the way she described the windblown dust raking the top of the tin roofs and the snap of the aloe leaves when she plucked them from behind the dump: this was the music she said she had grown up to, and it struck me that we all have different soundtracks to go along with our early years. Mine had been the sound of my mother’s footsteps at the top of the stairs, retreating to her bedroom, afraid to descend below.

At every traffic light in the city, men and women begged. More often than not, they were strung out and barefoot. The waiting cars clicked on their windscreen wipers and sprayed the air when the beggars approached.

I took a taxi to the city outskirts where the trees hugged the slopes. I didn’t want to join the tourists in the cable car, and I struggled my way up Table Mountain on foot, eventually found a quiet perch to look out over the sea. Nothing had prepared me for the wind and the rain and the sunlight that picked at my flesh, got into my bones. I had never seen weather so changeable before, even in the west of Ireland. I had brought a pair of binoculars with me. I trained them back toward the harbor, but it was impossible to see the Georges Lecointe, obscured by a giant white cruise vessel. The fog came in and the temperature plummeted, and I hurried my way down the mountainside, taking the last quarter mile in a darkness that seemed to rise from below. That night I walked the beach and saw a young woman in a long white dress stroll into the water. She was briefly apparitional. I made a slow circle, but when I returned, she was gone. I scanned the horizon: nothing. I half expected to see a group of rescuers leaning down to resuscitate her, but then it occurred to me that she had most likely stepped into the water out of joy or maybe some religious fervor, or else she had drowned. The city didn’t feel like it would mourn.

I retreated to my hotel. I had primed myself with a desire to go to sea, if only just to get away from it all, and so I phoned Brussels again. They told me that they would arrange a meeting locally and to expect a call from their chief of mission, John Conway, any day now.

At a certain stage our aloneness loses its allure. I waited for the call.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Twist, copyright © 2025 by Colum McCann. Reprinted by permission of The Wylie Agency.