Two Poems by Devon Walker-Figueroa

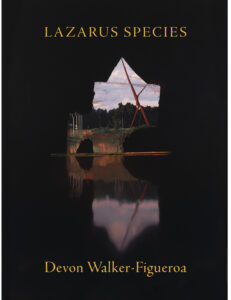

“Lazarus Species”

You don’t even need to be born

again in order to be born against

this riddled wall, each bayonet in love

with your bare, stigmatic neck.

Strange, the worst part is the waiting

to survive. Stranger,

let’s wait for the cave to act out

its name, invite the sun in

for the final rendezvous.

Oh to be you. Remember when you lived

in a century still

afeared of wild boars?

Now they march on Athens once again

to remind us how frail

our own endangerments. It’s a shame. I know.

You pay someone to puncture you.

The decades whir. Lost

is the TV show you watch

until there’s no season left

but the one caressing your window.

It’s overcast. It’s overkill.

Time to draw the curtains & play dead.

Once I was on a plane—

all ocean, blinding, down below—

a bald man seatbelted beside me.

He was high in every sense,

said, “I lived my father

alone to leave his life” & offered me

a hundred-dollar bill. “Here,

this is my business card.

Please stay in touch.

Please wear a toga to my funeral.”

Bad enough to find yourself

in a book of vanished things,

reports of vessels gulped down

by listless seas, whole farms smuggled up

into an Oklahoma sky. Now

to be born again & still

without one ounce of faith

in the durability of anything

but silk. I took the bill

& bought myself

a used priest’s robe

which I sometimes don

when I feel most prone

to survival & lament.

I, too, have not been seen

in years, so many years,

even the sycamores presumed me dead

& the boars began to dream

of meats far more exotic

than my own. Extinction is said

to be an event, but I can tell you nothing

is more uneventful—you find your family,

your whole phyla & future, buried

in some encyclopedia & glean

how small the risk of eternity,

how great the risk of not being reached for.

& under your entry, you find a man

discovered your decline & so became

famous by the standards of his day.

“There was no reasonable doubt,

the last individual had expired.”

So the search for you grows

exhaustive until it dies

down & no one watches the embers

but some canceled god, retired, forgetting

his own mellifluous names. I search

for my life as well, you know,

some passing evidence

besides the noise, which drifts about me,

so much exhaust inquiring, “Is this grief

the inexactitude we’d hoped for?”

*

“The Peasant’s Orgasm”

Three clear orbs fall across the blue edge

of my vision. Frail neural fables the retinae chase

after, I want to say, but can’t quite

catch. Meaning,

I fail to follow

the orbs’ trajectory (so often my own

thinking too) until these odd geometries

exit the visual

field. I asked my husband’s coworker once,

out of the blue, over

a business dinner,

what his consciousness felt like to him. His thoughts. I mean,

I said, is it colors ribboned with speech or

some other tumble of sensations

equally hard to articulate?

(Those aren’t the words I used

exactly, but you catch my meaning. I

mean, my drift.) He was so delighted

to be assigned

the impossible—to describe the clouds

of qualia crowding his brain case—

that he never resumed his discussion of loss

leaders, which in their way

have an operatic ring, though one that perishes

quickly in the corporate

lingo his tongue was freighted with. I got the sense

my asking him about his private

self—I mean, interiority—

its ineffable and peculiar

quality, led him ultimately from pleasure

to rage, though, which he soon directed

toward my husband. My husband,

who lovingly calls this man

“Hole.” I can’t confirm

the causal chain,

but out of his reveries, his healthy

reverence for his own mind, Hole—

who donned a hand-knit carmine cap—leapt

at my husband’s proverbial throat,

quite out of the blue, near yelling

in a rather upscale Italian joint

in DUMBO, under the distended shadow

of that huge foreshortened bridge, You know so much

about language, but you don’t know, not yet

anyway, the language of Design. The implication

being that Hole knew

the language of Design,

that Mars and Saturn and Jupiter were just

characters in a larger alphabet

my husband (also, I) could never read.

I’m of course exaggerating,

but the exaggeration feels true,

the way the northern lights do

even though they’re pure

distortion. A silence

then settled briefly

over the table, affecting the quality of precipitation

—I mean, snow—when it can be said

to sublimate, while Hole’s anger dissolved into the din

of diners—wine-drenched laughs, the delicate symphony of forks touching plates,

low murmurs suggestive of privacy and futility,

which reminds me

a slaughtered cow hung high to dripdripdrip,

and yet—

without preparation and wholly

beyond the reach of appetence, with its untold

motivational force

akin to that of pain

and the orgasm—devoured by the eye

before the mind can even hunger for it. Somehow

the conversation resumed while I was blipped out (toggling

between scenes

of chilly butcheries and subway cars, rib cages

of various life forms dangling

from metal rods), and the men

were now discussing matters

of taste, which seemed more appropriate to me than accusation, although

every discourse on taste is also a way of tasting the other’s

system of scrutiny. Fonts fell

under scrutiny. The sacredness

of some,

the profanity of others, and how

fonts could be paired

like certain meats are to fine wines. I wanted to know the fate

of Garamond, which I like best, for the almost “world” that closes

its utterance. My husband favors Futura, and I forget

Hole’s preference, though if I had to guess

I’d go with Helvetica.

It was only the first course,

and I wanted to reach under the table and do something obscene,

instigate, with a strategic touch, a timeless

sculptural desire in my husband, the way I used to do

to summon him, quite out of the blue,

into back-alley sex acts,

but my fingers felt bled of all strategy. I mean, intent. And I started to smell the tang

of blackberries as they shift

from fruiting to hoarding

carbohydrates in their roots,

and I saw the far-off fields

I grew up in overwrite

empire and dinner and the urban longing for what can no longer be retrieved

in its midst—the texture of clay-rich dirt

under my nails, all of it

crushingly sun-warmed and unlanguaged. Taste the grapes

whose insides would be forced

into rich flavors of oblivion

sommeliers might describe as “notes

of loam and asparagus”…swished and swirled

in a concurrent new-world

Italianate scene, though interred

under a rich layer of presence, the grapes pressed, in a future

now passed, by someone who will have been in possession

of the requisite milliondollar

press capable of translating fruit

into pleasure, if not

addiction and civility, whole Kalapuyan regions compressed into lines

curling over menus in New York. (To sell possibility

must be enough, those who designed me

taught me. To grow

the grapes, even if you have no means

of crushing them, is a living. Every peasant I’ve ever been or known

knows this truth.) Distraction

more than seduction being my

metier, I asked them both, feeling I might fortify their strained bond,

if either one of them were going to order

the rabbit because, if not, I would have to order it myself.

But this is wrong.

The memory is out of order.

Long before the yelling and the lustful soil came the rabbit.

Before the rabbit,

or long after it had been eaten

by Hole, I described, wholly off-topic, a course

I wanted to teach, called Wrong Science,

in which my students and I would digest untruths

that had entered this world in a diction of certitude

and with all the ineluctable fervor

of revelation. We would take turns

looking through the lead tube

of an early telescope,

watching the sun orbit our infancy,

suspecting

a distillation of all evil

to be crouched under our feet

instead of the lavatic rituals and shifting plates

the future, now the past, would finally acknowledge. You

could include a section on vision,

Hole suggested, and talk about mantis shrimp,

how they see all these colors we can’t,

colors we used to assume didn’t exist. But

how can we assume the absence of something whose presence we can’t even begin

to imagine? My husband answered, nostalgia

for the Garden or

the future, and then edited himself: future nostalgia.

And long before that, the longing for someone to ask, but not with words,

what is your thinking?

And what does it feel like

to hold its happening inside you?

In the middle distance imperceptible to language?

And why did you lie as a child

when asked if you saw ghosts, going so far

as to describe them as perfect

circles drifting through inner space,

by which you meant, the sky?

Someone, over dessert, dark

chocolate torte or maybe it was buttered artichoke, changed

the subject

to Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, the gaudy

shades of its presiding architecture—picture

the desert dabbed

with reds and golds and toxic-looking blues, the towering

implausibly pigmented likenesses of gods

who levied taxes and slew their serpent brothers.

I grew excited.

Hole lifted his wine glass to his mouth.

And it was red.

My husband was trying to chew and swallow

his cocktail’s greenish garnish, a leathery lime slice

dusted in orange pepper, and this made me fall

in love with him all over again, his curiosity that etiquette can never conquer. His

incorruptible

appetite for what may or may not be

digestible. All to say,

while the men replenished, I tried to describe a moment I’d never lived in,

when slaughter came to be

replaced—however nominally—by artistic representation,

as though the image had always been annihilation’s aptest understudy, just waiting

in the celestial wings,

and the buried pharaohs finally learned, deeply

as computers lately do, that meat carved with a stylus into a wall

kept far from worldly sight was far more tender

and delicious

than meat whose rot inevitably offered

a not wholly satisfying rhyme to their own. Digestion is also a form

of decay, my husband noted

somewhere along the line. And a movement

in architecture, Hole added. That’s concerned

with adaptation to shifting conditions. I noted

the care and strategy with which the tongues were often carved,

hanging from the cows’ mouths so the dead would not mistake for ornament

their perennial sustenance. The Greek influence

is so strong there, Hole might have said. You can see it best

in Alexandria. So I hear. All those archives

burning in fevered minds. History lost

in flames we can no longer read

or warm our hands by. Of course,

all of that’s likely fiction. The burning,

that is. A conquer so sudden and luminous it couldn’t even be seen

until it was over. Now they’re saying it was numerous fires spread

out over time. The conversation veered

to Plato then, as Socrates always knew it would, as he paced

the hemlock deeper into his dilating veins

while my future mouth watered at the thought.

I might’ve been that rare symposiast

who was also a woman, I ventured, uncertain

what shapes really related to what whirred

like alien weather behind my eyes. It’s true,

my husband verified. She’s a harpist—and former

bartender. She would have been allowed.

I could’ve poured the wine

and plucked the strings, I said. I could have

accompanied you.

So music transcends category, Hole said excitedly. I mean, gender. As in music

can pay your passage

to forbidden

places. Parties. Underworlds. Lives beyond life. I used to want to live forever

until I realized eternity would mean losing

everything anyway, the slow decay

of the wonderful, time digesting mystery

and misery like the same stale piece of cake, all of joy

and its aching origins and taxons

turning to dust in the grasp

of your ancient and unmurderable

mind. Space dust, my husband might have said. Space

as dust. Dust as mote or motive, I said. Yes.

It would be like witnessing your essence—

I mean, your whole soul—consumed

by what…all the distances inside it coming to

constitute it. Or

something…At the table next to ours a woman was discussing

monetizing her personality. Or maybe it was her lifestyle.

So many likes, she said,

on that skydiving post. Air thrumming in her ears, confiding

such elusive velocities. I want to say

it was something like three hundred.

More. A peasant skydiving in an alternate

century, growing so literate in distance and its breathtaking closure

that kings down on Earth began to swoon,

their gilded pleasure eclipsed

by a would-be swallow’s. I want to say

I’m remembering correctly,

that my husband did in fact order the hare.

Or maybe it was the coniglio.

That the same flesh passed over the two men’s tongues

though tasted of different animals because the tongues were divergent as were their fields

of blushing buds

and words. As for me, I forget the taste of

that night, and the more I reach for it, the less existent it becomes. So I look up

the orbs. It turns out they’re a sign

of detachment, the vitreous humor lifting…

“a sign,” the page I’m reading says, “of aging.” So I look up

at the orbs. As they fall—I mean, drift—

they lighten the bit of blue

they pass over. And lose dimension. Frail triad of contact

lenses descending through space

at the pace of snow

through the lower atmosphere. But I’ve seen these things

for as long as I can remember.

__________________________________

From Lazarus Species by Devon Walker-Figueroa. Copyright © 2025. Published by Milkweed Editions. All rights reserved.