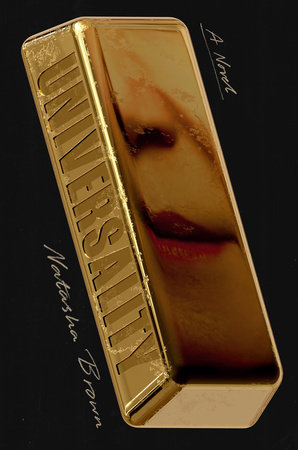

Universality

“WHY DON’T YOU HATE ME?”

“I’m busy, not everything is about you.”

“But surely this is about me. Claire. Look at me. Please, Claire.”

Richard watched as his wife—after all, she was still his wife—stopped wiping the counter and turned to face him.

“What’s gotten into you?” she said.

“I—I don’t know. I feel I’ve treated you badly.”

“You have.”

Wounded by this frankness, Richard gawped at her. He’d expected—oh, what? She had every right to despise him.

“What do you want from me, Richard? We’re here, we’re getting along. I don’t know why you’re dredging all this up again.”

Richard’s face crumpled. He coughed, craning away from her as he tried to choke the emotion back down. He’d never cried like this before, standing up in a brightly lit kitchen. He couldn’t bear it. Shoulders shuddering, he squeezed his eyes shut, willing it away. Then, her arms around him, the soapy clinical stinging in his nostrils from the cloth she still held. Pressing his face to her neck, he breathed in: earthy skin, unwashed hair, and Laundress-spritzed wool. The scent of Claire the mother, mothering him now as he swallowed his sobs.

“Come on,” she said, or whispered. “Come on.”

He sat on a barstool as Claire corralled Rosie for bed. The small child, who still had the absurd proportions of a toddler, was surprisingly articulate. She was not ready, she insisted, for bed. In a shrill and certain voice, she listed the things she’d rather do first. After naming five or six, she looked around the room for further ideas. Her eyes fixed on Richard, shining and unsteady, then continued past him to the dining area.

“Folding serviettes!” she shrieked, delighted at her novel idea.

Recognizing himself as superfluous to the bedtime routine, to his wife, her daughter, and their lives, he waved a wordless goodbye and left. He tried to close the front door gently behind him, but it was stuck. Yanking hard on the brass knob, he managed to force it shut. The resounding thud shamed him. Why wasn’t he around to fix this for his family? Because of him, his daughter would grow up in a house with stiff, awkward doors.

He could let himself back in and mend it, possibly even spend the night in a guest room. . . . Could they slip into a new, familial pattern? Claire might have him back, despite his publicized betrayals and her evident self-sufficiency. She was the type, he knew instinctively, to sacrifice her own happiness in favor of a veneer of normalcy for Rosie.

No, not just yet. He’d been offered a few soft landings—old colleagues and friends had, after his initial period of total radioactivity, reached out. In due course he would likely take one of these up, attempt to rebuild things. The story’s publication had been a career-limiting event, but he’d find a comfortable sinecure. It wasn’t the future he’d imagined for himself, but then, when did life ever bend to expectation? For tonight, he was content to wallow in the strangeness of his present circumstances, the fibrous edges of his old torn-apart life. “Like wet tissue paper”—where had that phrase come from? He grimaced, taken at once back to those awful antenatal classes and that grotesquely talkative woman who googled too much and blabbed even more. . . . Do you know what it means for a perineum to tear? she’d whispered to him before popping a custard cream into her little mouth. Then she’d uttered those words, flashing him with half-chewed biscuit—smugly certain that the image would take horrifying hold in his mind. Of everyone in their Kensington course, held in a windowless back room that usually hosted zero-gravity yoga, the woman had chosen Richard as her confidant. She’d spotted that he wasn’t quite like the others.

“I can’t stand her,” he told Claire after the class, steadying her arm as she took off her shoes and then dropped, exhausted, onto the sofa.

“She’s all right,” Claire sighed. “Just scared, and alone. I’m not sure I could hack it, going into that room week after week without you. You’re really good in there, really supportive. That’s probably why she’s so keen on you.”

Claire’s body had changed in the obvious ways, but he’d noticed subtle differences, too. He couldn’t find words to describe it; in photos from before, she seemed under-formed in comparison. Claire swiveled her feet up to the seat and eased herself onto her back.

“Well,” he said. “I’d better catch up on email.” Claire’s eyes fluttered shut and she nodded, then laid her head on the armrest. He took her left hand and kissed the backs of her fingers.

Those months whizzed past at fast-forward speed: finding the house in Surrey, packing up their lives, and moving in. Welcoming the baby. Four bleary weeks of paternal leave. Back in the office, exhausted, he couldn’t quite convince himself that it was all real. That picturesque home life. Perhaps it wasn’t; he never could adjust his self-image to that of a “parent.” Whenever he interacted with the baby, he felt fraudulent. Baffled by its inscrutable cries. The deepening bond of understanding between mother and child only excluded him further. Better to spend his nights in the city, he finally decided, than to come home late and intrude on their intimate domesticity. He took Claire’s lack of complaint as unspoken relief.

Turning away from the front door now, he drew in a sweeping breath. The evening was mild; he could walk to the station. Fluttering boughs of yellow-green leaves waved encouragement. He almost never experienced this time of day outside. Most of his evenings, like his mornings, had been spent breathing artificially cooled air in artificially brightened rooms. To notice the appeal of a balmy evening—that was progress, he told himself. This newfound calm, despite his persistent bouts of inexplicable crying, marked a step forward.

At first he’d felt violated. What he believed was a shared understanding, even trust, between him and that girl Hannah, had proved to be a cruel confidence trick. He couldn’t quite, not at first, hold the entirety of it in his mind, or see its full form—he was still up too close, still groping his way around a single edge of the violation. Despite this lack of perspective, he knew, or was beginning to understand, the magnitude of his fuckup. The grossness of her caricature, and its orthogonality to the truth of him, was stunning; he remained stunned as the perverse parody took hold within the British media.

He had tried, at the beginning, to counter the inaccuracies, naively believing that his tormentors had an interest in facts. A self-identified “fact-checker for the magazine” had emailed him to query his date of birth and surname shortly before the piece went online. Once he’d recovered enough fortitude, Richard had sent a new email to this fact-checker listing every issue with the piece: beginning with the claim that he owned a “solid gold bar” and ending with Hannah’s misuse of “begging the question.” No reply. Meanwhile, the inaccuracies—or, to call them what they really were, the lies—spread rapidly, amplifying with each repetition.

Eventually his efforts brought him to a cramped office, squeezed into the top floor of a building on a higgledy-piggledy back street near Oxford Circus. Hannah and her agent, Marie, had agreed to meet and discuss what Marie delicately termed his “concerns.” It was the first time he’d seen Hannah since their last interview, when she’d hugged him and told him to take care. She looked well. After the adaptation rights sold, she’d bought a house. He knew this because she wrote a personal essay on how home ownership had changed her taste in music, or painting, or something equally ridiculous. As far as he could tell, the authorial tone was not ironic. Had she ever truly opposed capitalism, or merely her own disenfranchisement? Not that the distinction mattered, he supposed, as long as the grievance could be monetized.

Home ownership hadn’t changed her views on him, in any case. A contemptuous smirk greeted him before she did. Presumably because his money didn’t come from appropriating other people’s lives. Or possibly, because people like her couldn’t secure art-preference-changing mortgages without people like him, who provided statistical confidence that the debt wasn’t totally worthless. He knew that smirk; it was the same smirk he’d seen directed at his father and at all the grubby people who constructed houses—whether out of bricks and mortar or through securitization.

He looked again at Hannah. Clearly some man had shoved his hand up her skirt—or worse, hadn’t—and now she was taking it out on him, ruining his life. That was an ugly thought, the sort of thought her pathetic caricature might think. He regretted it. But also, after reading such a distortion of himself, how could he not think it? How could he ever exist as a person, separate from that article, again?

“You said you wanted to get to the truth,” he began after the terse pleasantries, letting indignation swell within his chest. “But half of what you wrote was just made up. It’s libelous.”

“ ‘The truth’ is ambiguous.” Marie swooped in before Hannah could speak. “It’s not absolute. Hannah’s journalism was a composition of multiple accounts, or ‘truths,’ creating a complex picture for her readers to interpret. Her journalism is no less true, no less honest, for its plurality. In fact, I think it’s more honest. More of a reflection of how the world really is—outside of your privileged bubble.”

“Privileged?” He shook his head at that. “Not everything is a culture war. Some things just are, and others aren’t. Some things were, some weren’t. We must be able to agree on that much, at least.”

Tilting her head to the left, Marie absently whispered something to Hannah, who nodded and stood up reluctantly, avoiding the hazardous piles of books and papers as she charted a path out of the small room.

“Look,” Marie said, once Hannah had closed the door. “I’ve listened to some of the recordings. You don’t come off well. I don’t think ‘releasing the tapes,’ here, or whatever your retribution fantasy is, will go in your favor. You’re hardly a sympathetic character.” With a slight nod, Marie pointed through the door’s window to Hannah, who was at that moment struggling with a coffee machine. “Besides this adaptation deal, she’s got nothing. But, despite all the self-pity, you’ve still got lots to lose. Alazon magazine’s parent company is a major news organization. If you bring a libel case against them, they’ll completely exhaust your financial resources and destroy whatever’s left of your reputation. They will drag you through the mud. In the end, you and Hannah will both end up with nothing, though she can always write a contrite personal essay and get back to her old life. She’ll be fine. What will you do then, exactly?”

He could think of nothing to say. Without his corporate exoskeleton, he found himself appallingly vulnerable and more avoidant of conflict than ever. He barely managed to keep from crying as he sat there. He sniffed, shrugged. It was hopeless. Swathed in scarves and shawls, with silvery hair cut to just above her shoulders, Marie looked like she had the capacity for kindness. She used it then, sweetening her voice to a conciliatory coo.

“I tell you what. Give it another month or two, and this’ll blow over. Really. If the show goes ahead, and that’s a big if, they’ll use a different name for your character anyway. Something less . . . well, you know. None of this is about you personally, it’s just a good story. Bread-and-circus stuff. A shiny new diversion will come along soon enough. Here’s what I think, Richard. Not that you asked, but I’ll tell you all the same. Here’s what you do next: Go home to your wife and daughter. Wait this out.”

She let out a tinkling little laugh.

“Oh,” she said on Hannah’s reentry, raising an amused brow at the precariously balanced trio of coffee mugs. “I don’t think we’ll need those after all, will we, Richard? We’re just about done.”

__________________________________

From Universality by Natasha Brown. Copyright © 2025 by Natasha Brown. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.