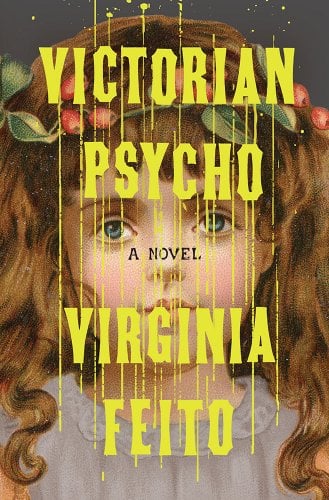

Victorian Psycho

Acquaints the Reader with the ‘Incident’ Which Transpired at the Clergy Daughters’ School and Which Led to My Subsequent Education at Home.

I chance upon Miss Lamb repeatedly the following days and by ‘chance upon’ I mean I follow her and observe her through keyholes as she polishes grates. Over three consecutive days I ring the bell sixteen times. It is always Miss Lamb who comes, her presence offered up so effortlessly that I begin to suspect the house is bestowing her upon me as a gift. Or is it that Miss Lamb is offering herself, wishing to delight me with her subservience?

I am not used to having a friend. They so often don’t last.

Growing up, it was rare that I made the acquaintance of other schoolgirls, as I was mostly educated at home (although I enjoyed journeying the six-mile walk to the nearest girls’ school to stare at the pupils and play ‘Count the consumptives’).

For a brief spell, however, I did attend a school for the daughters of clergy – until the Incident. The school was nestled in a wide valley between neighbouring hamlets. I still recall, with the nostalgia of an escaped convict, the pitchers of frozen water which we had to crack open with our knuckles for our morning ablutions. The cold that whisked our breaths into visibility so that the shared bed-room looked like an opium den. The film of grease over our milk, which was warmed in filthy copper pans.

The institution proudly advertised ‘No holidays’, and we were not allowed any trips home during the school year. It trained the daughters of clergymen for lives as governesses and teachers, for a substantially low fee (substantially low to the point of ridiculous, to the point where one wonders if it was all organised in jest by the trustees, proposing numbers as dares, slapping their thighs and chortling in the snug of the pub).

The girls at the school were quiet and weepy or boisterous and angry, and all seemed wary of me. They refused to meet my eyes or allow themselves to be touched. One of them possessed a chocolate-coloured mole lodged between her nose and cheek. It was as round and fat as rabbit droppings and I tried to taste it, once, but she pulled away, bowing her head anxiously.

The Reverend had been keen for me to attend, but after the Incident, he went to great lengths to hide the fact that I’d ever been there. What was the damned Incident, I hear you ask? Well, a terrible fuss was made of it, but, really, it could have happened to anyone.

We were making a doll to be presented to the organist, who was retiring after decades of service and untoward advances towards generations of schoolgirls.

I was peeling off scabs and shoving them into the sawdust stuffing of the doll – which was to be dressed in a tiny version of our uniform, much to the organist’s delight – when I spotted a black crow through the cracked window glass, perched in a tree. At that very moment, it just happened to drop dead, slamming onto the mossy floor.

Permission to roam the grounds was rarely if ever granted, so I waited until nightfall to fetch it.

The night warden drank from a bottle of sherry she kept in her desk and would fall asleep long before the last of the girls. Most were too frightened to take advantage of her drunken slumber, preparing themselves for the perpetual martyrdom that was to be their lot in life.

When I crept outside, the damp evening air soaked my flimsy nightdress, dragging me down with the strength of five pulling hands as I waded my way to the spot where I had seen the bird fall. I kneeled and groped in the darkness until my fingers were met with the brush of feathers. The crow had fallen from that tree on purpose, I thought. For me.

I cuddled the bird at night, combing its glossy black feathers, like a mane of human hair, with my fingers – something the girls wouldn’t allow me to do to them – and secured it under a loose floorboard beneath my bed by day.

The crow was still rotting under the bed by Easter Sunday – the stench it exuded not offensive enough, in the airy room, to be attributed to anything more sinister than a group of growing girls who lacked water to dab at their underarms.

I had wilfully blotted a writing exercise to merit a flogging. Miss Petty was lazy and her legs heavy with gout, which meant I was to fetch my own instrument of torture. This allowed me to steal away to our bed-room to retrieve the crow and slip into the empty refectory unnoticed.

I lay out the bird, wings spread, on one of the platters, and arranged food on top of it to disguise the writhing maggots, digging my fingernails into the putrid flesh and flicking bits into the pudding.

I collected the bundle of tied twigs from the supply room and returned to the school-room, where Miss Petty birched my neck a dozen times for the blotting, and another dozen for my delay in retrieving the instrument. A girl sitting to my left sketched the pink, rose-shaped bruises that bloomed on my neck until the bell for lunch was rung, and she and the others streamed into the hallway with expectant stomachs.

After saying grace and singing a hymn, we dug in. The girls were so hungry they barely paid heed to what they were spooning into themselves. They pawed at the bread, shovelled potatoes onto their plates, and tore into greyish meats. Plaits were flung over shoulders or tucked into collars to avoid soiling. A spoon clanged to the floor, a wooden bench creaking as one girl leaned over to retrieve it. One of the older girls cleared her throat while drinking, spurting sipped water back into her glass. Sauces dribbled from the corners of mouths, stained white pinafores, browned noses, slid under fingernails. My eyes hovered over all, waiting for the crow to strike. My crow. My friend.

There was a panic, at first, that it was cholera. In the glorious tumult that broke out in the night, the girls vomited black, sweet-smelling treacle, along with brimstone – the preventative medicine we were spoon-fed each morning. The girls purged left and right, meaty spew leaking through the floorboards, bits of which would eventually have to be scooped out with spoons and knives.

The school had been so intent on protecting its students from autoeroticism – expelling any girl they believed carried ‘the vice’, forbidding us from consuming warm food or enjoying blankets for fear of arousing our passions – they were blindsided by this particular atrocity.

They couldn’t prove I’d had anything to do with it, but as I was the only healthy child, and because the Reverend did not seem surprised to be called on – he merely sighed, closed his eyes, and nodded as he listened to their accounts – suspicions were strong enough for them to invite me to leave.

My time at the Clergy Daughters’ School was cursory, but the experiences I lived there will remain with me until the day I die, right until the very moment I look down upon the shadow made by my dangling feet on the gallows floor.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Victorian Psycho: A Novel by Virginia Feito. Copyright (c) 2025 by Virginia Feito. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.