What if HIM from The Powerpuff Girls Was a Genderqueer Barista?

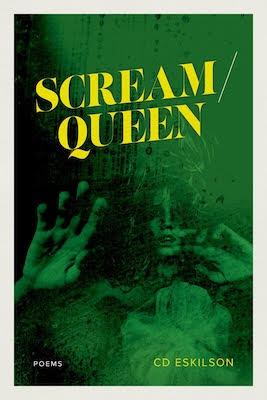

“I chafe against a want for what is owed: / a movie in soft focus with warm colors, / perfect lighting, every scream queen / flagrant with her brilliant smile,” writes CD Eskilson in their imaginative and playful debut Scream / Queen, which interrogates monstrosity and the monsterification of trans, queer, and disabled/mentally ill bodies through the lens of pop culture, particularly horror films. The collection juxtaposes classic horror tropes—demons, jumpscares, haunted houses—with the real-life horror of transphobia and legislation targeting trans youth, as well as the more nuanced horror of inherited familial traumas.

Inhabiting a wide range of personae and formal traditions, Eskilson imagines a world in which HIM from The Powerpuff Girls is a genderqueer barista, Icarus posts thirst traps in drag on their finsta, and the women of the speaker’s family twirl into the teal waters of the Aegean Sea like Meryl Streep in Mamma Mia!, unburdened by their ghosts. By radically re-envisioning familiar characters and tropes, Eskilson breathes new life into their stories, granting them agency and also allowing readers who have been marginalized or flattened by harmful language and representation to see themselves reflected, perhaps for the first time. Scream / Queen is a testament to the liberatory power of queer imagination, creating “Not simply / a new ending, an entirely new script.”

I spoke to CD over Zoom, where we talked about queer origin stories, mythmaking, and the subversive potential of monsters.

Ally Ang: What was your first introduction to the horror genre and how did you come to fall in love with it?

CD Eskilson: I’ve been interested in horror movies, monsters, and horror as a concept since I was a little kid. For some reason, I was really enamored with monsters. I have memories of, before going to kindergarten, watching The Wolf Man on VHS or Creature from the Black Lagoon. I became fascinated with the more technical aspects of movie-making when I got to undergrad. I was a Media Studies minor in addition to being an English major. As I became an adult, rather than just being like, Cool, monsters! I was more like, How do these movies get made? or, What stories are they telling? So much horror today, like I Saw the TV Glow by Jane Schoenbrun, tells stories in really subversive or unexpected or radical ways. Monsters as a concept can be this liberatory radical utterance against the thing that’s being made into a monster.

AA: Yeah, totally. I was a scaredy cat as a kid, but I felt that same pull towards creatures and monstrous beings as I got a little older. I think a lot of queer people do.

CDE: For sure. I think it’s a sign, right? Everyone’s always like, Yeah, I was really into monsters as a kid too. And then I ended up being a trans person. Being in marching band is another big thing, or playing an instrument in general.

AA: Let’s start with the titles of both the book itself and the sections within the book, all of which take particular tropes and subgenres within horror (found footage, body horror, jump scare, etc.) and divide them with a slash. The slash can be interpreted in a lot of ways (the term “slasher” immediately comes to mind), but I was hoping you could tell me how you decided to structure these sections and what the slash signifies for you.

CDE: So within the sections themselves, the poems speak back—whether directly or in an emotional or lyric sense—to the titles. The BODY/HORROR section talks a little bit about chronic illness and the experiences of the trans body. Other sections, like FOUND/FOOTAGE, are a little more abstract, more like making sense of the past, childhood, experiences of dysphoria that you didn’t know were dysphoria, trying to figure out where you got to the point of realization about your identity.

With the slashes, I’ve been really interested in how language works and how we connect to and identify with words. In the book, you start with FOUND/FOOTAGE which is two words, and as the book progresses, the last section, SUPER/NATURAL is one word that’s been divided. There’s this forced rupture in the word, but we can still identify it as the word. I’ve been thinking about that as a way of interrogating binaries, thinking through the ways in which we put up these arbitrary distinctions between parts of a whole or a spectrum. It’s a way of interrogating that violence and exploring how we can continue to identify something that’s had this violence enacted on it. And “slasher” is something I’ve been excited to see people pick up on. It’s that forceful happening within language and how we can resist it or make something new out of it.

AA: Scream / Queen doesn’t only use horror movies as references, but also Greek mythology, including Medusa, Icarus, and Geryon, imagining them as contemporary queer figures. What led you to draw upon that particular mythology, and where do you see the parallels between Greek mythology and contemporary horror?

CDE: Another thing I’ve noticed is that a lot of queer and trans folks I know have an interest or obsession with Greek mythology as kids. To be a linguistic nerd for a second, the word “monster” comes from the Latin “monstrare,” which means “to demonstrate.” So quite literally, monsters demonstrate something, which is very similar to a myth. It’s supposed to point towards this social truth. In the case of Medusa, who’s typically portrayed as a monstrous figure from the ancient past, there’s a resonance with monsters and horror movies today. And with Icarus, I was wondering what other story could be told about that figure? How could it be revised or reimagined to say something new that still speaks back to the idea of flying too close to the sun, defying expectations, defying possibility? I’ve been thinking through myth and horror as drawing from a similar idea, if that makes sense.

AA: There’s a moment in “During Intro to Film Theory” that really struck me—when talking about the real life horror of legislation targeting trans youth, you write, “What angle could I / film from to grip an audience and capture / all the care inequities? Without red dye, / people shrug, stay unfazed by our loss.” The weight of that responsibility as a trans person to make our humanity visible and legible to cis people is something that really resonated with me, and I’d love to hear more about how you thought about audience while writing this book. Did you feel the impulse to try to represent transness in a way that cis people would understand, or was that something you didn’t think about or actively rejected?

CDE: I think that’s really important to be thinking about as someone writing into identity or writing towards something that’s very personal and also very political at this particular moment, with the giant magnifying glass that’s on trans folks today. As I was writing the book, I wanted to imagine my audience as first and foremost trans and non-binary folks, particularly trans youth. The audience is also anyone whom language has othered or marginalized in some way and who are interested in reclaiming and revising the stories and language that are leveled against them. When I was writing, I was contending with the idea of language as something that can be so violent and so creative at the same time. It’s not like it’s inherently benevolent. We have to be part of the process of interrogating it, forming it, creating new forms of language that see us or help us be who we feel we are. I definitely wrote this as a way of hoping or praying for continuation of survival for trans folks, but hopefully it also allows people to see the radical performance that language can do outside of that—for folks who are neurodivergent or chronically ill as well. Hopefully people can see the possibility that can open from that.

AA: In “At the Midnight Show of Sleepaway Camp,” the speaker attends a showing of the film Sleepaway Camp with a group of queer friends who have differing reactions to the film’s big twist in which the main character is revealed to be a trans girl. You write, “Can’t we / hold both readings of the movie to be true? / Know there’s risk in our vindictive gore / but that it offers a resistance.” Later, in ”My Roommate Buffalo Bill,” the character of Buffalo Bill is presented as a confident, self-actualized trans woman in contrast with the speaker, who is more insecure and earlier in their transition. Can you speak more about your relationship to films like Sleepaway Camp, Dressed to Kill, The Silence of the Lambs, which contain depictions of trans women that could be considered transmisogynistic, problematic, or harmful? Do you think films like these are reclaimable or redeemable?

The audience is anyone whom language has othered and who are reclaiming and revising the stories that are leveled against them.

CDE: Horror can be an incredibly reactionary and violent space for a lot of folks, particularly trans folks, like with the trans panic trope going back to Psycho and Dressed to Kill, which also comes up in the book. I spend a lot of time thinking about these movies and what impact it has to see that or to see people so interested in that. When people decide that “The Silence of the Lambs did nothing wrong” is the hill they want to die on, it can be very frustrating.

In terms of reclaimability, I think that’s what the project of the poems, these reimaginings, is. With questions about whether a movie like Sleepaway Camp has a redeeming quality, I think a lot of that is for trans folks to decide whether that’s a piece of media they want to engage with. But for me, writing these poems, I was thinking how I could reimagine these characters as having the lives they wanted to live or as being recognized as a trans woman, which The Silence of the Lambs blatantly does not do. The way I’ve reckoned with that is by creating a reinterpretation, like making a movie into a myth—you know, how myths have so much revision around them, where we tell different versions of the stories. So mythologizing it allows me to participate in the storytelling or make it something I can claim ownership over.

AA: Yeah, that’s similar to how a lot of young queer people are so drawn to fanfiction.

CDE: Yeah, very similar to that. Fanfiction allows for the possibility of participating in the story in a way that allows queer folks to see themselves, like queer fanfiction about Twilight.

AA: I love that. Those reimaginings were my favorite poems in the book. I don’t have a question about this poem, but I just loved “Update on HIM from Powerpuff Girls.” I think that was my favorite one.

CDE: Yeah, HIM is so special, at least for me as a kid. Talking about introductions to horror, I remember being completely terrified of HIM and also utterly transfixed every time HIM was onscreen. I’m always excited that people loved HIM so much.

AA: Another major theme of this collection is the speaker’s relationship with/inheritance from their biological family; in particular, a mentally ill father and grandmother, an uncle who’s passed, and a sibling who is also queer/trans. The presence of these family members and their impact on the speaker’s life and sense of self feels like a kind of haunting, which is explored most directly in “Our Family Leaves the Haunted House.” But I wanted to talk about the last poem in the book, “Draft Message to My Sibling after Top Surgery.” I thought this was a beautiful place to end the collection, with the image of the speaker and their sibling running along the shoreline of a beach side by side. How did you decide to make this the final poem in the collection?

CDE: That wasn’t originally the last poem; I think I previously had a different one in the same section, but it was still towards the end in very early drafts. There was a certain point when I realized that horror is such a big part of the book—it’s where we start, and so much time is spent talking about monsters and the horror of certain experiences. In wanting the book to present some sort of growth or journey, I figured it would open things up more to end outside of that genre, looking beyond the confinement of haunting or monstrosity. Just being alive and being aware of one’s body through something like top surgery or the experience of being on the beach. It felt like a very natural place to end, returning to a place that feels safe and full of possibility.

AA: Are there any horror films or characters that you wanted to write about but didn’t make the manuscript?

Fanfiction allows for the possibility of participating in the story in a way that allows queer folks to see themselves.

CDE: One that I got really held up on that I didn’t know what to do with outside of the title being fun was this 1950s monster movie that’s just a bunch of Cold War propaganda, like The Blob—it’s called Them! and it’s about giant ants; they take over the town in a way that’s a veiled anti-Communist message. But the title was really cool.

I really like watery monsters—being from Southern California on the beach, I spent a lot of time thinking about what could live in the water—so I had a The Shape of Water poem that sort of just fizzled out because I like Creature from the Black Lagoon better and I couldn’t do both. I had to pick and my heart lies with Creature from the Black Lagoon. Sorry, Guillermo!

It was interesting thinking of what didn’t “make the cut” in terms of what kind of story I wanted to tell or what different angles to present monstrosity from. I’ve still been hung up on Greek myths, so I’ve continued to write about that after the book and carried stuff over that didn’t end up in the book.

AA: I guess that’ll be in the next one! Those are all my questions; is there anything else you’d like to mention that you didn’t get to yet?

CDE: I think the biggest thing as we move through this time is to continue to support trans and non-binary writers and people, especially Black trans and non-binary folks. And being mindful of how the things in the book are things that happen to people. Poetry is also speaking to a lived experience. So support people through books and in daily life through mutual aid and organizing as well.

The post What if HIM from The Powerpuff Girls Was a Genderqueer Barista? appeared first on Electric Literature.