What My Father’s Emails Taught Me About the Craft of Writing

The computer lab where I checked my email was in the basement of Cornell’s Electrical and Computer Engineering building. A windowless room with thin, industrial carpet that felt like a second home. There was a vending machine outside the doors where, for under a dollar, I could buy a strawberry Pop-tart for dinner. Picking at the treat, breaking off the crunchy corners first, saving the gooey middle for last, I’d log into the portal where I knew an email from my dad was waiting. Then I’d get to work, crafting my reply.

My dad is a writer, which was why I never wanted to be one. According to my mom, this was the reason we were always poor and he was rarely around. He ran a small, independent publishing company which is how he made money, and, though we never really discussed it, he must have written books on the side because every now and then one would show up in our house.

My dad was an artist, my mom explained, and when you’re an artist, art just flows out of you, you can’t do anything else. It’s not that she approved of the hours he spent in his office, leaving her to raise us mostly on her own—they fought regularly, separating when I was fifteen—but it must have at least served as an explanation. His tendencies were outside of anyone’s control. It was simply who he was.

Art did not just flow out of me, like my mom said it should—often I had to force it out with the will of an ungodly spirit.

An artist was decidedly not who I was, according to this logic. I could do other things, namely math and science—pretty well, it turned out—and so I did, happily. Being an artist, let alone a writer, seemed like the dumbest thing in the world. It paid no money, offered no benefits (we didn’t have health insurance until I was a teenager, when my mom became a teacher after going to night school), and demanded all of your free time.

As a kid, I wanted to do whatever paid the most money. When it came time for college, I amassed considerable debt in order to attend an Ivy League School (which I assumed was necessary in order to be rich), and chose the major with the highest starting salary. Someone in the family needed to build a safety net.

Studying electrical and computer engineering in the early 2000s felt like inhabiting a foreign country, and not a particularly pleasant one. Most of my classmates had somehow been coding for years. Being the only girl in most classes, I kept to myself, studying and working alone, afraid that if I didn’t know something it would prove what I assumed the boys were thinking—that girls weren’t meant for this.

The emails from my dad were an oasis. With a cheerful tone and dry wit, he’d check in on my academic happenings, signing off with a paragraph of encouragement. But the heart of his letters was the commentary in between, op-ed style musings that felt pulled from the Times, personalized just for me. His thoughts on political happenings were razor sharp and darkly funny. But his fixation on politics didn’t stop him from waxing long on the brilliance of, say, Battlestar Galactica, or a new dish at the local Chinese takeout spot. What struck me most, what I could feel, even then, was the lyricism in his notes, a rhythm that made you feel as if you were singing the lines.

Before I was born, my dad was the frontman and songwriter for a band. It’s lore in our family that his band, which included my mom—whose love and influence, I should note, is so vast and expansive it would take a lifetime to detail—played at CBGB’s and had the same manager as the Ramones. As a kid, I’d sit beside him at the piano, his whole body shaking as he pounded Chuck Berry on the keys—watching, learning.

My dad wrote military history, which meant that, as a child, I could not have been less interested in his work. It also meant that I was not surrounded by literature, like one might imagine for the “child of a writer.” There was no Dickens or Dostoyevsky in our house, and we couldn’t afford encyclopedias or National Geographic. There was a bookshelf somewhere but I hardly remember it. My dad kept his work in his office, a space that doubled as a living monument to The New York Times and the Civil War. Every inch of the newspaper-lined space looked as if it were covered in a sepia filter thanks to a coat of yellow cigarette smoke. At home, he mostly stuck to Star Trek.

A tomboy growing up, I cherished time with my dad. Sunday mornings, when he was home, I’d make him toss tricky math challenges at me across the kitchen table, the way I’d beg him to give me “divers” when we’d play catch in the backyard. He’d sit in his usual spot, with his coffee and cigarettes, meticulously paging through each section of the paper, while I read over the funnies, studying The Far Side, in particular—his favorite.

After my parents separated, he moved out and our already limited time together was cut further. He wasn’t exactly gifted at “building a home,” so anytime we met, we did so over an occasional lunch at the local pizza place. Our emails were a return to a closeness I’d thought was lost.

How can I explain that though, now, at forty-two, on the verge of publishing my debut novel, a book I poured my soul into for years, the idea of being a writer in that dreary Cornell computer lab was the furthest thing from my mind? At that time, I considered fiction a waste of time—I wanted to do and make things, not sit around and read. It’s amazing how our minds jump to our defense; my curriculum didn’t make space for electives, none of my (exclusively engineering) friends were the least interested in literature, and anyway, there was no money in writing, so it was easy to rationalize the whole enterprise as unchallenging and inferior. I put blinders on, and that allowed me to keep going.

All to say, I was not conscious of any style or form or scholarly value in our emails beyond the primary and all-consuming goal of constructing a response that would impress my dad. To be clear, I felt no need to dazzle him with facts. Never did I pretend to know much about politics, that had always been his terrain, and his pride for me academically was never in question. If a prize were to be had, it was in the telling, whether it be about a new dish at the cafeteria or an annoying coworker at my work-study.

My dad is fiercely opinionated, but, importantly, he is not a snob. He never graduated college, yet remains one of the smartest people I know. While performing at CBGB’s, he drove cabs on the side. The number of times he brought a literary eye to a dorky, network television show are too numerous to count. With him, the most accessible pleasures are often the most appealing. Only in retrospect is it clear how freeing this was as I unwittingly approached creative writing. I could rant, unashamed, on whatever captured my attention, as long as I found a way to entertain. Occasionally, he’d cop to cracking up at one of my emails and I’d feel as if I had unlocked a sort of magic. Strangely, it felt like my favorite part of coding, the rare wave of pleasure after toiling over a messy algorithm, a sort of profound quenching, when, at last, everything was in its place, and all ran smoothly together.

Our emails continued after college, though fewer and further between. The subject line was always (and still is) the day of the week in which the email was sent, which offers a kind of simple, thoughtful appeal, typical to my dad’s sensibility. For as long as I’ve known him, he’s worn the same thing each day, only the color of his sweater changing, and lives off the same three-pronged rotation of meals. I’d be lying if I said this predictability didn’t thrill me. I wear a uniform as frequently as possible and would eat the same meal all week if this habit didn’t drive my boyfriend crazy. Radical predictability in everyday minutia allows us to focus on what matters most—the writing.

A few times, as an adult, I’d open one of his books. Though full of dates and wars and General names I didn’t care to remember, I immediately saw my dad’s mind at work between the facts. I couldn’t help but smile seeing how clearly he came to life on the page. But when I tried to read the book in full, I couldn’t last more than a few minutes. This was where his time had gone, I thought, the words packed with his wit and insight. I was jealous of the book, and put it down.

*

How does someone learn to be a writer? The most common and accepted answer is to become a reader. When we consume writing we love, we internalize the language, structure, and cadence; like living abroad in foreign-speaking country, phrases can’t help but rub off. This can be most affecting when we’re young and impressionable. Most writers I know spent their formative years steeped in books, learning their taste, studying the classics, and forming a sensibility, while my brain was firing on digital logic, object-oriented code, and fourier transforms. Whatever early reading was needed to make someone a “writer,” I assumed, had surely passed me by.

Looking back, I wasn’t entirely new to the writing thing. In so many ways, I’d been studying it all along.

Still, I wasn’t surprised when, a decade after graduating college, an itch to write started to prickle. By that time, the internet had transformed media and everyone was clambering to get their thoughts online. But I was surprised, almost disbelieving, that when I eventually put fingers to keyboard, something seemed to click. This is not to say the words flowed easily, or that anything I wrote was exceptionally good. My vocabulary was nonexistent, my work was full of grammatical errors, incoherent until many rounds of edits. But if I stared at the words long enough and searched the thesaurus hard enough, I could make a piece of writing work, and, importantly, somehow, I could tell when it did.

The first essay I ever published was an attempt to distract myself from emailing a man who broke my heart. Perhaps it comes as no surprise that drafting lengthy letters to ex-boyfriends eventually became a foundational habit; my dad and I dodged emotions like bullets in our notes, so I hurled them at other men in my life. I’d toil over drafts for hours, days, sometimes weeks, trying to articulate my feelings just right to the man on the receiving end. It wasn’t until my sister, tired of my pleas to edit these spiritually pitiful drafts, gently offered, “What if you wrote for yourself, instead of for these guys?”

I spent months on that first essay, which no one but my sister read (god bless her herculean heart). But completing it felt like stepping into another dimension. It offered the same gripping pleasure as crafting an email—articulating observations, weaving in arguments, attempting to make it all sound easy and rhythmic—only far bigger, not limited to a single man’s approval. Writing, for me, had always been confined to letters, which offered an excuse—at least someone would read it—but had a way of masking the fact that it was, actually, writing.

I wrote in secret at first. Though my work required me to lead meetings with rooms full of men twice my age, and I had just graduated from a top ten business school, the thought of attending a writing workshop in any form left my paralyzed in fear, sure I’d be laughed out. My whole life, artists, writers, had seemed a different species, separate from me. Art did not just flow out of me, like my mom said it should—often I had to force it out with the will of an ungodly spirit—and it was not the only thing I could do. It took years of devouring novels, catching up on all I’d felt I’d missed in college, writer-podcasts perpetually in my ear to understand how “they” worked—and if, maybe, I was one of them—until I finally mustered the courage to sign up.

As it happens, I did not die of embarrassment. I was met with acceptance and kindness; the women in that first workshop went on to become some of my closest friends. In classes, the mechanics of writing began to reveal itself, like seeing the secrets behind a magic trick, things I’d sensed, spelled out explicitly. My piece even got a few laughs, many notes, too, but not any more or less than others. Strangest of all, people said I had a strong “voice.”

I’d become familiar with this term as I’d thrown myself into literature. I understood its weight and the elusive nature of cultivating it. I remembered how quickly I felt my dad in the pages of his own books, how much soul he was able to convey in a few well-crafted lines. If my voice was anything, it was the shadow of his. His emails were the furthest thing from my mind in that first class, I had busied myself reading the classics and studying techniques. But looking back, I wasn’t entirely new to the writing thing. In so many ways, I’d been studying it all along.

My dad, like so many writers I now know and love and thoroughly identify with, is not the savviest of social creatures. Growing up, he never answered the phone, so we’d have a secret code when my sister and I called his office—ring once, hang up, then ring again. After my parents’ separation, I mourned his presence in my life, a presence that receded immensely without the forced interactions of a shared home. It would take decades to realize the weight of his continued impact, demonstrating, even in distance, the power of writing, the most accessible of arts, to turn a day around, deepen a bond, and even act as a lifeline, by showing up as best he could and in the way he knew how.

__________________________________

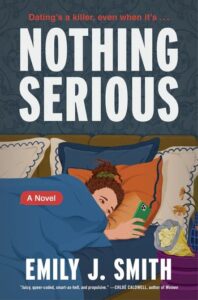

Nothing Serious by Emily J. Smith is available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.