What the Work of Literary Production Reveals About the Resonance of History

The work: at first the work is difficult. Later, the work is also difficult. In between, I lose track of myself. Mostly because I am writing about the end of the world, or the end of a certain world, and because here I am, in the aftermath, writing in a quiet room, with a view of the forest, and the world is still going. People ask—my family, my therapist, my students—how is the work?

Because in the work, ghosts have appeared, the dead are moving between walls, a woman meets her double in the basement of a hotel in Montreal, a man waits in a train station every day for a year for his daughter to arrive back from the dead. In the work, a man buys two motorcycles—one for himself, and one for God. In the work, maybe, everyone I’m writing about is dead and not dead at the same time. It will take almost eight years to figure out the answer to this question. In my diary, I make notes about the work: what am I working on?

In my book, the dead are talking—they are calling across a room or a city, or they are just beyond the wall making a noise in their world loud enough so that we might be able to hear it in our world.

Also in the work: many Jews, all of the Jews, four very specific Jews. My family asks, in your work, are you writing about our family? Mostly, I deflect. My hearing is very bad, and I tell them I can’t hear the questions correctly. Or I say: talking about writing is boring. Or I say—the work is ongoing, its still ongoing, its distressing how ongoing it is. A year later, two years later, nine years later, the same people ask the same question about the work, but the answer is different. The work is everything, and the work is heartbreaking.

*

I recognize now, from a better distance, with better hearing, that I was also working from a place of obsession. First—the very end of Jewish Vienna, the music of Gustav Mahler; who was a Jew who had to stop being a Jew in order to make music; his Kindertotenlieder; or the short, smuggled burst of Klezmer in his First Symphony; or a recording of his Ninth Symphony made by the Vienna Philharmonic in January 1938 two months before the Anschluss, a recording in which Mahler’s former student Bruno Walter takes the final movement uncharacteristically fast, almost twice as fast; it is hard not to hear it and to think the players are in a hurry to get somewhere; at least nine of the musicians on stage that night were eventually murdered. Leonard Bernstein once compared this final movement, which is marked esterbend, or dying away, to the way a heart beats as it nears death, the way it loses rhythm and breaks apart.

Or I became consumed with the village where my family came from: first with its Yizkor book, its book of memory, a copy of which is held by the New York Public Library. I became consumed with the men in that book who all have my grandfather’s face. Or, a black and white image of the village’s river, a picture which, some mornings, I swear momentarily turns to color in front of me. At a certain point while I was working, Google drove its cars through the village’s streets, and I was able to do something I had no desire to do in my actual life, which was to walk around this place, this speck of green emerging from the deep past. From my desk, the village scared me even to see in pictures. Seeing it this way meant, however, that I could walk on its road, which was not really a road, or I could walk beside the old synagogue, which still existed, but only in pieces: every window was broken a hundred years ago and nothing had been repaired.

Before, all I knew of this place was the way it had died—thirty-eight years after my family left this place for America, every remaining Jew in the village was killed on a single night. Deaths squads marched the community to a nearby airfield and the Jews were shot one by one. In the pictures, from my desk, the village is a ruin, but is a green ruin. Obviously, the village has been photographed in summer. The trees are heavy. The river—my great-grandparent’s river—is still and blue. I’ve read that often the cars that Google hires to photograph places like this go in the early morning, when people are not yet awake. Maybe this is why the village is entirely empty, why there is no evidence of any human life. Although, in my memory, this is how it’s always been—everyone has always been gone.

*

By the time I found these pictures, I already knew the basics of the novel I was making, which was about the Alterman family, a family from Vienna who had both survived the war and who had not survived the war. The novel is split into four sections, one for each member of the family, and in each section of the novel, the member of the family narrating is the only person who has lived. Writing it this way meant that I was writing both their life and their death and also their afterlife, and the places, too, where these ideas sped up or slowed down or broke apart into pieces. A mother is alive, writing about the loss of her daughter; and then the daughter is alive, writing about the memory of her mother. This was my idea for the novel all along—that in creating a book that tempts the reader to believe in impossible things, that the horror of history might feel new to them when those impossible things do not arrive.

By then, I have understand something essential about the history—no matter how often we are told of the awful past…the hope remains that we have heard the story wrong.

In the middle of all of this—I move to the woods. In the woods, it’s easier to feel heartbreak and distress. Or at least, one can practice the art of distress and heartbreak without having to be so quiet. Also, I get my hearing fixed. For a very long time before this I had not been able to hear properly. A long time: most of my life. This part is maybe not interesting: in crowded spaces, in certain quiet spaces, when there was wind, when there was especially quiet music, beautiful music, I could not hear. When more than one of my family members were speaking I could not hear any of them. I could not hear while I was teaching, or while I was trying to listen to someone else teach. I had, until I was forty-three never understood anything ever whispered to me in confidence.

The doctor who ran my initial tests told me, when we fix this you’re going to hear birds now. A sentence I laughed at. Of course, I’d heard birds before. But he was right. Afterward, the world is too loud. Do they ever stop? I asked my wife about the birds one of the first mornings afterward. Meaning: are they always like this? Always going? Always calling for us?

In my book, the dead are talking—they are calling across a room or a city, or they are just beyond the wall making a noise in their world loud enough so that we might be able to hear it in our world. In the waiting room of my audiologist, I make the final notes about the book. The office where I make these notes is not far from where my great-grandfather is buried. Also, it’s not far from the classroom where I teach. Before this I had never noticed how often I talked about the work in terms of hearing, or listening. Even at the very end of the process, it is still difficult. When my family asks, when my students ask, when strangers ask, I have nothing new to say.

Although by then, I have memorized my way around the shtetl. I have memorized too, the way the last movement of my favorite pieces of music rush to escape death. By then, I have understand something essential about the history—no matter how often we are told of the awful past, its miseries, its catastrophes, its ruination, its madnesses and slaughtering, the hope remains that we have heard the story wrong, that some essential truth has gotten lost in the transmission; surely not the whole village, not everyone, not the entire city, not the babies, not the graveyards. Surely we’ve heard it wrong.

Alone in the small dark box, a voice tells me to press a button when I hear the noise. I ask what I think is a good question: what exactly am I listening for?

__________________________________

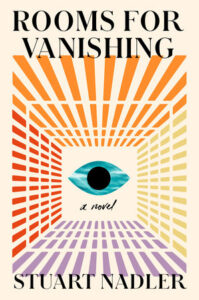

Rooms for Vanishing by Stuart Nadler is available from Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.