Why are we so obsessed with political cartoons?

On January 3rd, Washington Post cartoonist Ann Telnaes left her post after charging her publisher with censorship.

In a Substack letter, the artist explained her reason. Her editors unceremoniously dropped a piece poking fun at “the billionaire tech and media chief executives who have been doing their best to curry favor with incoming President-elect Trump.” The subjects included several devils you know: Mark Zuckerberg, Sam Altman, Patrick Soon-Shiong, and Jeff Bezos.

“I’ve never had a cartoon killed because of who or what I chose to aim my pen at. Until now,” Telnaes wrote to her followers. Her resignation has since become part of a wave of high-profile departures, from the Post and other mastheads. Though as an artist, her political protest is singular. Which has got me thinking about her medium of choice.

Where did political cartoons come from? And when and why did they sync up with journalism?

*

They technically started as broadsides, an English street phenomenon. But like the bifocal and the glass harmonica, the newspaper-friendly, American spin on the political cartoon originated in the skull of Ben Franklin.

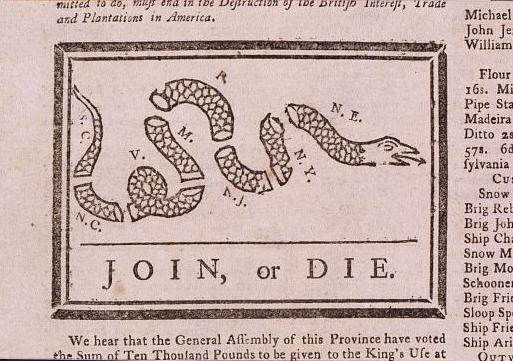

In an early edition of his own paper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, Franklin launched the now-infamous “Join or Die” slogan with a woodcut of a segmented snake. Intended to rally the colonists during the French and Indian War, this image would prove indelible.

Ben Franklin (1754)

Ben Franklin (1754)

Though now you may see it most often on flags straddling militia-bound Jeeps.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the newspaper cartoon gained popularity on both sides of the Atlantic.

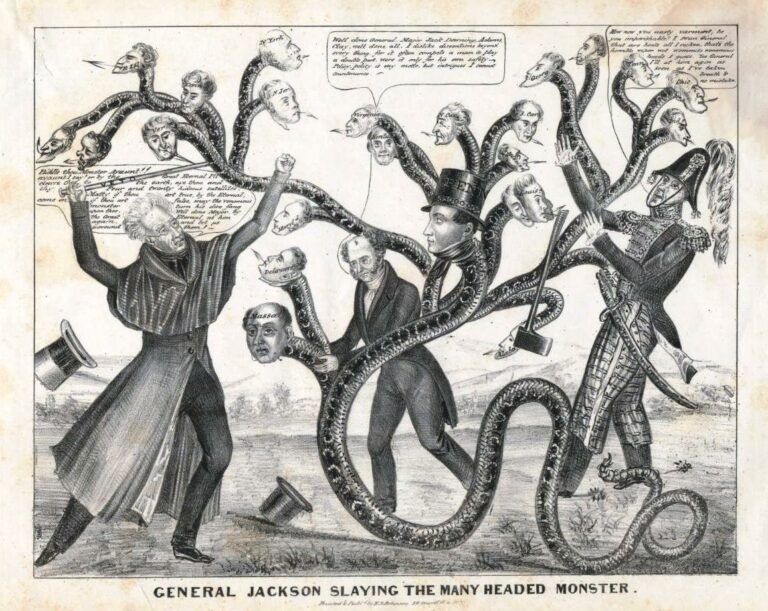

Henry R. Robinson (1836)

Henry R. Robinson (1836)

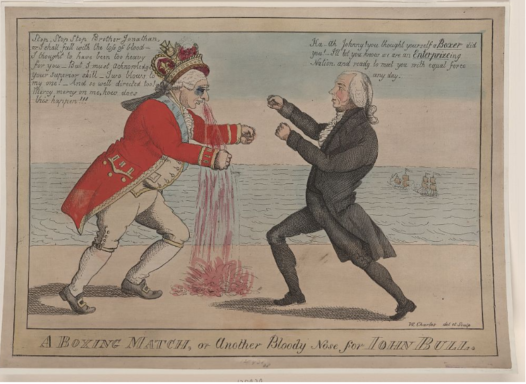

Working in the William Hogarth idiom, British caricaturist James Gillray took festive jabs at Napoleon in Punch magazine. And in America, the likes of James Akin, Henry Robinson, and Thomas Nast took swings at the national banks, the Republican party, Boss Tweed, and King George III.

Charles Williams (1813)

Charles Williams (1813)

It’s in the late 19th century that the form starts to develop a consistent tone. Artists hurl stones at presumed Goliaths from either end of the political spectrum. And a cheeky, sort of anarchic voice starts to overpower the high-handed symbolism.

You can trace a line straight from this kind of thing to the goony, feigned innocence of Alfred E. Neuman.

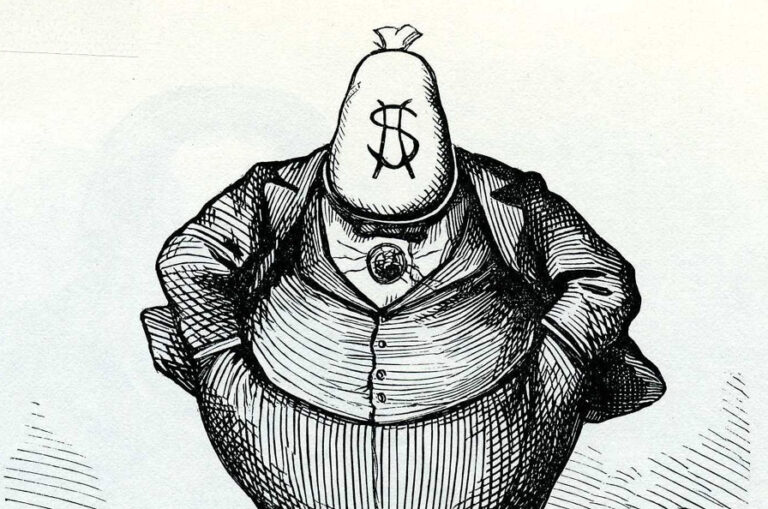

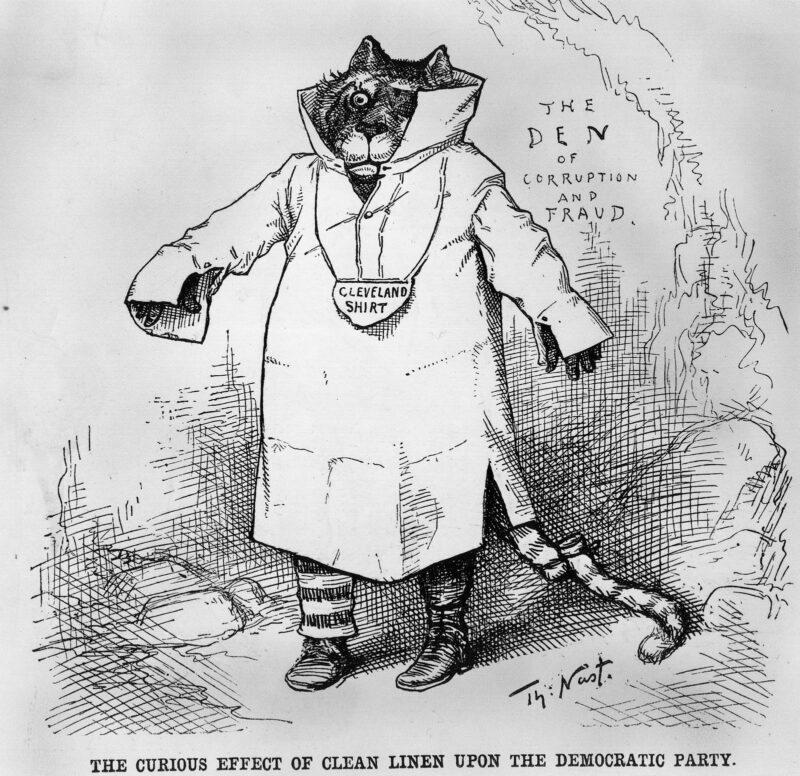

Thomas Nast, in his Tammany Hall era.

Thomas Nast, in his Tammany Hall era.

In the 20th century, political cartoonists lean further into that disruptive ~esprit~. A moderate populism reigns supreme, maybe best emblematized by the ultra-popular work of “Herblock.”

But again—from both poles—you also find a “Just Asking Questions” kind of negging. Which bears out formally, too. The medium, with its seeds in caricature, slides easily into racist and sexist portrayals. And certain artists really start to put the broad in broad-side.

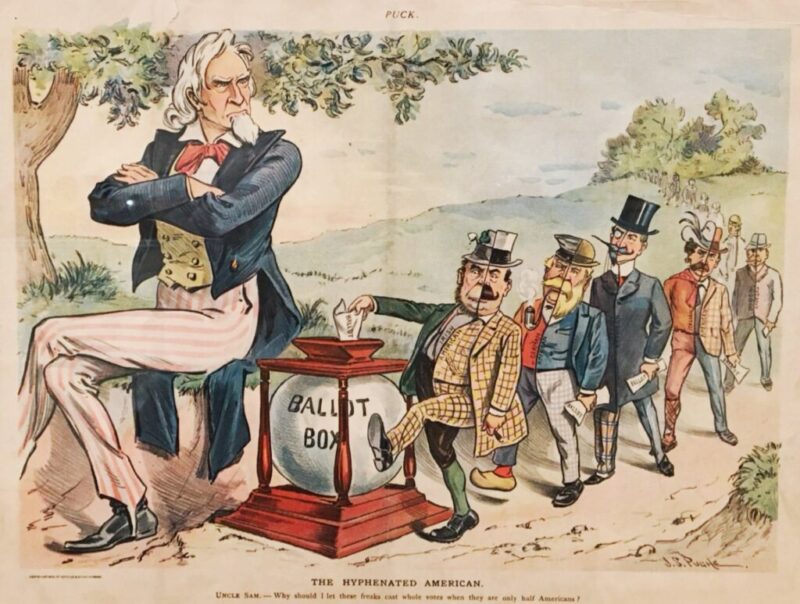

J.S. Pughe/Puck Magazine (1899). An early bit of anti-immigration sentiment.

J.S. Pughe/Puck Magazine (1899). An early bit of anti-immigration sentiment.

According to the First Amendment Museum, around 1950 “newspaper advertisers and publishers began exerting more of an influence over political cartoons.” And as digital media increased a cartoon’s reach and lifespan (if not its artist’s salary), persecution became a vivid threat.

In 1999, Robert ‘Bro’ Russell founded Cartoonists Rights, “the first global human rights organization” dedicated to protecting cartoonists who’ve been targeted by their arguably humorless subjects. In 2006, a similar mission called Freedom Cartoonists is born from a UN summit on intolerance.

In 2015, the grisly Charlie Hebdo murders—carried out in response to a cartoonist’s taboo depiction of the Prophet Muhammad—rocked the global press. Today, orgs like Reporters Without Borders document cartoonist intimidation alongside other threats to journalists.

This is all to say that as long as political cartooning has been tied to the newspaper, it’s enjoyed an unusual space in the culture. We sanctify images that by dint of their form aren’t meant to be taken seriously. They create the rare occasion where we leap to defend, even respect, the rights to mock, to poke—to troll. Often as not from either side of the aisle.

It’s brave to speak out of turn. We love free speech. But, if you’ll forgive the cliche—they say a picture’s worth a thousand words. What can a cartoon do to, say, Jeff Bezos? On the one hand, maybe nothing.

But we’ve also seen it put out a king’s eyes.

*

On Substack, Telnaes emphasized how seriously she takes her satire. “As an editorial cartoonist, my job is to hold powerful people and institutions accountable.” This is a noble and heavy mandate. But as much as I support it in theory, in ~esprit~ I’m still wondering what accountability can look like, as our institutional watchdogs continue to fail.

For another angle, consider “Riss” Saurisseau, a cartoonist who survived the Charlie Hebdo massacre. “Satire has one virtue that has got us through these tragic years—optimism,” he told the BBC this January, which marks the tenth anniversary of the attacks.

“If people want to laugh, it is because they want to live.”