Why Bob Dylan’s COVID-Era Album Was the Real Nobel Lecture

Admittedly, lies, fear, muddle, fury, the dead and their ghosts, were everywhere. Admittedly, everything was pretty fucked up.

This is what I remember, by way of situation.

Shortly after midnight on March 27, 2020, when Bob Dylan dropped his surprise single—“Murder Most Foul”—America, the world, and my body tracked multiple, interlocking crises. Coiling through some 16 minutes, 55 seconds, the song was his longest ever, and his only release of original writing since Tempest in 2012. The front page of the New York Times the next morning would read, “JOB LOSSES SOAR; U.S. VIRUS CASES TOP WORLD,” as CNN signaled “Trump’s approval up amid coronavirus concerns.” Compounding insinuations of apocalypse, California’s governor Gavin Newsom would soon declare a parallel climate “state of emergency,” and wildfire season promised to reel into the worst of recorded history. By year’s end, some 9,917 fires scorched more than four million acres, accelerating flash floods and mudflow. “Murder Most Foul” was the first of three such stealth releases—“Multitudes” followed on April 17; “False Prophet” on May 8; and ultimately an entire new album, Rough and Rowdy Ways, on June 19. Juneteenth: the holiday that memorialized the date Union Army General Gordon Granger posted the order that “informed…the people of Texas…all slaves are free.” By then, June 19, 2020, witness videos would record Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin as he pressed George Floyd to the ground, and knelt on his neck for at least 8 minutes and 15 seconds, even after Floyd lost consciousness and paramedics arrived. Floyd’s murder would inspire the largest racial justice collective actions in the United States since probably the civil rights movement.

While I was in Tulsa, researching this book at Dylan’s archive, and introducing a dear friend, the writer Lucy Sante, at a reading sponsored by the Bob Dylan Center and Magic City Books, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Until we secured flights home, Lucy and I worried—fantasized—accepted—that we’d be trapped in Tulsa for the duration, the city then in high throttle, often honorably, sometimes disgracefully, towards the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, a year into the future.

Mixing and juxtaposing voices, lingos, and tones, [Dylan] traces the decline of America over the trajectory of his own lifetime through the kaleidoscope of the Kennedy assassination.

We returned to New York just fine, but I knew something was wrong. By early June I would be diagnosed with a precarious illness that over subsequent months would demand manifold drug therapies and serial surgeries. One operation persisted fourteen hours, a sort of sci-fi marvel of science, internal engineering, and medical dedication, contra all the coeval dystopian breakdowns of that first COVID year. As in a seventeenth-century poem by John Donne, George Herbert, or Andrew Marvell, the fraught human body is a microcosm, a mirror to the larger disintegrating world spirit. Many of us started to feel like we were living in the future, a future predicted by scientists and historians, but that arrived faster than expected. But who would live to see that future through?

Dylan’s dead-of-night note that attended “Murder Most Foul” appeared to acknowledge the pervasive civic tumult—as though his new record might actually engage the specific American instant, a prospect at least as startling as the song, for by consensus Dylan had vacated this stance in 1964, when he told Nat Hentoff no more “finger-pointing songs,” and “I don’t want to write for people anymore. You know—be a spokesman.”

Greetings to my fans and followers with gratitude for all your support and loyalty across the years. This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting. Stay safe, stay observant and may God be with you.

A “while back” turned out to mean…February. So named for the scene early in Hamlet when the ghost of the king commands his son to “Revenge his foul and most unnatural murder,” the song takes as a point of inflection the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, whom “Murder Most Foul” will also dub “the king.” (Closer to home, Congressman Ben Butler of Massachusetts declared at Andrew Johnson’s 1868 impeachment trial that “By murder most foul [Johnson] succeeded to the Presidency, and is the elect of an assassin to that high office, and not of the people.” Dylan is captivated by America’s presidents—on “Must Be Santa” he even augmented the routine list of reindeer with a rhyming litany of chronological commanders-in-chief: “Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon,… Carter, Reagan, Bush, and Clinton.”) As Dylan eases into his opening lines, revelation vies with deception, facts with rhetoric, and doggerel tilts into brute eloquence:

’Twas a dark day in Dallas—November ’63

The day that will live on in infamy

President Kennedy was riding high

A good day to be living and a good day to die

Being led to the slaughter like a sacrificial lamb

Say wait a minute boys, do you know who I am?

Of course we do, we know who you are

Then they blew off his head when he was still in the car

“Murder Most Foul” is, first, the story of a killing, which Dylan depicts as an execution, and, then, a catalog of the plangent reverberations for a nation—as he later sings—in “slow decay.” Dallas strictly speaking was dark when Kennedy arrived, rainy and gray, and from the outset Dylan embeds the assassination inside prior American cataclysmic cruxes: Native American ethnocide (referencing the Oglala Lakota saying, “a good day to die”) and Pearl Harbor, via Franklin Roosevelt’s “Day of Infamy” speech. But 1941 was also the year Dylan was born, and his song is just as cannily personal as it is historical. His memoir Chronicles recounts his mother’s avid response to a Kennedy campaign visit to Hibbing, Minnesota, six months after Dylan left for Minneapolis and the University of Minnesota. “He gave a heroic speech, my mom said, and brought people a lot of hope,” Dylan wrote. “I wish I could have seen him.” Kennedy also figured into one of Dylan’s first public controversies when, on December 13, 1963, he ruffled his Emergency Civil Liberties Committee hosts in New York after they bestowed upon him their annual Tom Paine Award—for civil rights efforts—by remarking that “I saw some of myself” in Lee Harvey Oswald. More recently, Dylan included paintings of Oswald and Jack Ruby in his “Revisionist Art” series (2011-2012), both modeled after reconfigured Life magazine covers. On his twenty-first-century albums, “Love And Theft” (2001), Modern Times (2006), and Tempest, Dylan circulated several conspicuously political songs, among them “High Water (For Charley Patton),” “Cry a While,” “Sugar Baby,” “When the Deal Goes Down,” “Workingman’s Blues #2,” “Ain’t Talkin’,” “Scarlet Town,” “Tin Angel,” and “Tempest.” During an interview with novelist Jonathan Lethem, he might jest, “You know, everybody makes a big deal about the sixties. The sixties, it’s like the Civil War days. But, I mean, you’re talking to a person who owns the sixties. Did I ever want to acquire the sixties? No. But I own the sixties—who’s going to argue with me?” Still, on “Murder Most Foul” Dylan thwarts readymade nostalgia, an easy revisiting of the storybook sixties and his golden “spokesman” moment. Instead, mixing and juxtaposing voices, lingos, and tones, he traces the decline of America over the trajectory of his own lifetime through the kaleidoscope of the Kennedy assassination.

Greil Marcus once proposed that the “engine, the motor, of Dylan’s best work is empathy.” The empathy that prompted him as a young man to identify even with Oswald here disperses any single dominant narrator into a hypnotic succession of irreconcilable speakers: a dazed JFK; his smug killers (“Thousands were watching, no one saw a thing…Greatest magic trick ever under the sun”); clueless Oswald (“I’m just a patsy like Patsy Cline”); genial Nellie Connally, echoing the last words Kennedy heard (“You can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you”); Mary Pinchot Meyer, JFK’s rumored lover, herself later murdered, also execution-style; exponents of indignant reason (“Don’t worry Mr. President, help’s on the way”); playboy, police buff Ruby (“I’m in the red-light district like a cop on the beat”); and finally the devil, who transforms the assassination site into Robert Johnson’s crossroads: “Dealey Plaza, make a left hand turn / Go down to the crossroads, try to flag a ride / That’s the place where Faith, Hope and Charity died.”

As Dylan logs the assassination and its aftermath, he insistently intertwines politics and culture, history and religion. He calls up November 22:

The day that they killed him, someone said to me, “Son,

The age of the anti-Christ has just only begun.”

Air Force One coming in through the gate

Johnson sworn in at two thirty-eight

He glances at Parkland Hospital, and Kennedy’s autopsy:

I’m leaning to the left, got my head in her lap

Oh Lord, I’ve been led into some kind of a trap . . .

They mutilated his body and took out his brain

What more could they do, they piled on the pain

But his soul was not there where it was supposed to be at

For the last fifty years they’ve been searching for that

Freedom, oh freedom, freedom over me

Hate to tell you, Mister, but only dead men are free

Send me some loving—tell me no lie

Throw the gun in the gutter and walk on by

For this net of loose talk tightening to verse, Dylan can sound random—his quicksilver associations—and formal: rhyming couplets, intricate stanzas, deft repetitions. Here the president links a recent ideological pivot (“I’m leaning to the left”) to Jackie cradling him in the death car, while around them a tune from My Fair Lady, “On the Street Where You Live,” slides into “Oh Freedom!,” a Reconstruction-era spiritual that Joan Baez performed at the 1963 March on Washington. Kennedy’s own anguished voice stiffens into the icy charm of his shooters, ultimately to arrive at a sort of choral lament for his missing “soul,” and the nation’s, equal parts Little Richard, Dione Warwick, the Everly Brothers, gangster movies, and Jessie Jackson.

Throughout, Dylan just as aggressively—and casually—blurs eras, movements, and historical figures: the sixties, nineteenth-century English Romanticism, the Civil War, Shakespearean kings, the fifties, Jim Crow, and the Bible. During the introductory movement, his shrouded titles and misty, half-remembered phrases from a broken world conjure up a meditation on impermanence, where the present is all there is. Then, his fragments sharply coalesce into a marathon radio playlist, a chanted litany of requests to DJ Wolfman Jack, perhaps broadcasting from across the Mexican border on station XERF, with a signal so powerful the Wolfman could reach Canada:

Play me a song, Mr. Wolfman Jack

Play it for me in my long Cadillac

Play that Only the Good Die Young

Take me to the place where Tom Dooley was hung

Play St. James Infirmary in the court of King James

If you want to remember, better write down the names

Play Etta James too, play I’d Rather Go Blind

Play it for the man with the telepathic mind

Play John Lee Hooker play Scratch My Back

Play it for that strip club owner named Jack

Guitar Slim—Goin’ Down Slow

Play it for me and for Marilyn Monroe

And please Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood

Play it for the First Lady, she ain’t feeling that good

Over seventy-five, maybe eighty songs in all: and not only songs, for the Wolfman apparently plays movies, Broadway shows, and books, too. Radio is the medium of “Murder Most Foul,” and perhaps Dylan’s preferred medium as well. In Chronicles he recommends New Orleans radio, suggesting “WWOZ was the kind of radio station I used to listen to late at night growing up, and it brought me back to the trials of my youth and touched the spirit of it. Back then when something was wrong the radio could lay hands on you and you’d be all right.” On “Murder Most Foul” Dylan himself is also a sort of medium; as the songs unspool he might as well be taking down messages from the dead over a Ouija board. During a 1997 interview, he related the radio to Orpheus in the underworld, with an echo of Jean Cocteau’s Orphee. “Well, America was tied in with the radio when I grew up…Radio stations were all over. It was a large area and transmitters could transmit thousands of miles….The radio connected everybody like Orpheus or something…. When I grew up, that’s what you listened to.”

Despite Dylan’s stately vocals, and the elegant trio of keyboards (Alan Pasqua, Fiona Apple, and Belmont Tench), “Murder Most Foul” is a farrago of slippery locomotion. History implodes into puns—Guy Banister and David Ferrie, the alleged assassins at the center of New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison’s Kennedy investigation, are introduced as though they were hit tunes by British Invasion bands: “Slide down the banister, go get your coat / Ferry ’cross the Mersey and go for the throat.” Similarly, the Warren Commission, and its single-bullet theory: “You got me dizzy Miss Lizzie, you filled me with lead / That magic bullet of yours has gone to my head.” History erodes metaphor—“When you’re down on Deep Ellem put your money in your shoe / Don’t ask what your country can do for you.” “Deep Ellem Blues” is a song with a pedigree stalking back to the 1920s. Dylan even recorded a version during the sessions for his 1992 album of covers, Good as I Been to You. But Deep Ellem is also a historic Black Dallas neighborhood. History saps cliché—“Living in a nightmare on Elm Street” may sound rote, except Kennedy actually was gunned down on Elm Street.

So many songs, poems, novels, films, and gags. Subtexts align like filings around a magnet. Elizabeth Bishop famously said she preferred poems that register the “mind in motion” rather than “at rest,” and nowhere in “Murder Most Foul” does Dylan’s mind relax. His couplets—stitched together by a rhyme—typically saunter in contrary directions. That magnificent liturgy of American popular culture since the Second World War? Dylan’s vocals mourn as he celebrates—those unrivaled accomplishments in the arts were solace and distraction. Wolfman Jack’s “speaking in tongues” is babble and prophecy. Easy for a listener to go missing in the claustrophobic torrent of names and associations on “Murder Most Foul,” and many earnest annotators did. That might be the craftiest twist of Dylan’s design: his song forces us into the paranoia of conspiracy theorists, running down clues, Easter eggs, synchronicities, accidents, and suspicions, a dead-end Pynchonesque quandary. Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 calculated our “extended capacity for convolution,” and Dylan here mocks and cautions us together. Tag the quotations, he dares us. Overlook the coup.

Yet touchstones of his twenty-first-century music survive his formidable now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t skepticism. Following Modern Times and Tempest, “Murder Most Foul” restages American history as the history of crime. Through the aperture of the Kennedy assassination, Dylan scans minstrelsy—“Black face singer—white face clown / Better not show your faces after the sun goes down”; the Civil War—“Play the Blood Stained Banner”; and Jim Crow—“Take me Back to Tulsa to the scene of the crime.” Echoing “Love And Theft,” he situates race as the nucleus of the American dynamo, and racism as the original American sin. And all through “Murder Most Foul” he accents the urgency of memory: “If you want to remember, better write down the names.” In this Dylan resembles James Baldwin, who warned, “History is not the past, it is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we are literally criminals.” But by reminding us in “Murder Most Foul” where the bodies are buried, Dylan is circling back to another locus classicus of memory, Cicero’s de Oratore:

There is a story that Simonides was dining at the house of a wealthy nobleman named Scopas at Crannon in Thessaly, and chanted a lyric poem which he had composed in honor of his host….

The story runs that a little later a message was brought to Simonides to go outside, as two young men were standing at the door who earnestly requested him to come out; so he rose from his seat and went out, and could not see anybody; but in the interval of his absence the roof of the hall where Scopas was giving the banquet fell in, crushing Scopas himself and his relations under the ruins and killing them; and when their friends wanted to bury them but were altogether unable to know them apart as they had been completely crushed, the story goes that Simonides was enabled by his recollection of the place in which each of them had been reclining at table to identify them for separate internment; and that this circumstance suggested to him the discovery of the truth that the best aid to clearness of memory consists in orderly arrangement.

He inferred that persons desiring to train this faculty must select localities and form mental images of the facts they wish to remember and store those images in the localities.

Who’s calling for those records from Wolfman Jack? “What is the truth and where did it go,” Dylan, or someone, asks, maybe the ghost of JFK, or anyone’s ghost. Probing the afterlife of a grave crime, “Murder Most Foul” radiates a twilight kingdom that by the close feels posthumous. “I can’t remember when I was born and I forgot when I died,” as Dylan will sing later on Rough and Rowdy Ways. The final request is for Wolfman Jack to play the song we’re already listening to, and which presumably then will broadcast into eternity.

Amidst the national debasement, corruption, and murdered magistrates—other songs will rouse Lincoln, McKinley, Nixon, and Julius Caesar—Trump is nowhere, and everywhere. In his only interview about Rough and Rowdy Ways, with historian Douglas Brinkley for the New York Times, Dylan hinted at his concerns, aspirations, and contexts. His album wasn’t “nostalgic,” but contemporary, current. “I don’t think of ‘Murder Most Foul’ as a glorification of the past or some kind of send-off to a lost age,” he apprised Brinkley. “It speaks to me in the moment.” Of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, he confided, “It sickened me no end to see George tortured to death like that. It was beyond ugly. Let’s hope that justice comes swift for the Floyd family and for the nation.” COVID-19 impressed him as a “forerunner of something else to come. Extreme arrogance can have some disastrous penalties.” Correlating “Murder Most Foul” to a folk tradition of “songs about people,” Dylan broached yet another assassinated president, “Mr. Garfield.” Replying to Brinkley’s question about the obvious intimations of mortality in his new songs, he intensified the stakes. “I think about the death of the human race…I think about it in general terms, not in a personal way.”

During that charged spring of 2020 as I replayed Rough and Rowdy Ways, a notion took hold, a notion Dylan himself all but conceded in the incisive candors, pivots, and speculations of his talks with Brinkley: the album is his acknowledgment of his 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature. A few days before the Swedish Academy deadline, Dylan finally did deliver a Nobel Prize Lecture, as required, on June 4, 2017. He spoke his solid, rhythmic prose over Alan Pasqua’s piano, à la Jack Kerouac and Steve Allen. Yet his official address proved lax: summaries of classic books—Moby-Dick, All Quiet on the Western Front, The Odyssey—and a misattribution of some lyrics by a later songwriter to Charlie Poole.

On Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan also reemerges as a restless, sometimes cordial, often corrosive analyst, agreeing at last to engage—if not fully to explain—the whats, hows, and, possibly whys of his creative life.

Rough and Rowdy Ways, I came to believe, is his real Nobel Lecture—a lecture from inside his own forms and idioms, from inside the same artistry that earned Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize. On two songs, he even references the gold medal he received at a private ceremony in Stockholm. When in “My Own Version of You,” Dylan’s mad biological engineer boasts, “I want to do things for the benefit of all mankind,” he’s impishly glossing a line adapted from the Aeneid and inscribed on the back of the Nobel Prize medal: Inventas vitam iuvat excoluisse per artes (or in William Morris’s 1876 translation of the Virgil original, “and they who bettered life on earth by new-found mastery”). On the medal, the Virgil inscription surrounds a young man sitting under a laurel tree, listening to the Muse, and writing down her song. He is among those in “Mother of Muses” whom Dylan imagines uttering sweet entreaties: “Sing of honor and fame and glory be / Mother of Muses, sing for me.”

From his initial 1960s New York press coverage onward, Dylan refused any public clarification of his songs, opting for deadpan, put-on, or ridicule. His twenty-first-century recordings advanced strategies of embodiment; he resisted routine statements and singer-songwriter epiphanies for relentless collage. He might write narratively about the Civil War in “ ’Cross the Green Mountain” for the Gods and Generals (2003) film soundtrack, but ultimately Dylan tended to lodge the legacies of empire, slavery, criminality, sin, the body, desire, and his own autobiography in volatile verbal echo chambers of harmonizing and clashing reverberations: Ovid, Homer, Virgil, and Milton; Shakespeare; Henry Timrod, the poet laureate of the Confederacy; Robert Burns, Lewis Carroll, Mark Twain, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Flannery O’Connor; Junichi Saga’s Confessions of a Yakuza and Memories of Silk and Straw; Charley Patton, Robert Johnson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Muddy Waters, Dock Boggs, Leroy Carr, the Carter Family, the Stanley Brothers, Hoagy Carmichael, Bing Crosby, and Billie Holiday; W. C. Fields, the Marx Brothers, and assorted film noirs.

Yet on Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan also reemerges as a restless, sometimes cordial, often corrosive analyst, agreeing at last to engage—if not fully to explain—the whats, hows, and, possibly whys of his creative life. Suddenly, he sounds direct, or almost. Those intensive collages implied, and even staged, his successive incarnations across six decades of musical self-reinvention. But on Rough and Rowdy Ways Dylan could sing, bluntly—albeit while quoting Walt Whitman: “I contain multitudes.” Nearly as blunt, “Murder Most Foul” frames an account of his origins in global war, national trauma, and the tilt-a-whirl popular culture of the forties, fifties, and sixties. Making art is the axis of every lyric here, and his catalogs incline also to allegory. “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You” embraces all at once God, a lover, and Dylan’s audience. In “My Own Version of You,” his gifts for materializing a fresh world out of shards and scraps of the past tip into Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein:

I’ve been visiting morgues and monasteries

Looking for the necessary body parts

Limbs and livers and brains and hearts

I want to bring someone to life—is what I want to do

I want to create my own version of you

“Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” localizes spirit, imagination, and the yearning for transcendence. For “Mother of Muses,” Dylan entreats Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, and categorically affirms the epic aims of Rough and Rowdy Ways. “I’m falling in love with Calliope.”

“Murder Most Foul” was Bob Dylan’s first number 1 song ever on a Billboard chart. No other new music I can remember from that fierce spring and summer—no art of any strain, novel, film, poem—so infiltrated and permeated the furors of COVID-19, George Floyd, climate horror, Trump, and death.

Dylan was about to turn seventy-nine years old, and when the pandemic lifted just enough for him to take Rough and Rowdy Ways on the road in the fall of 2021, he would be eighty. During those early virus days, younger musicians again looked to him, for their own COVID projects. Bon Iver performed “With God on Our Side” on a Bernie Sanders Livestream event. Daniel Romano recalled Dylan’s 1984 appearance on David Letterman when, backed by the Los Angeles Latino punk band the Plugz, he performed a few songs from his then latest release Infidels. Romano eventually re-recorded all of Infidels as a raging what if/fuck you: Do (What Could Have Been) “Infidels” by Bob Dylan & The Plugz.

Emma Swift and Chrissie Hynde produced the sharpest Dylan lockdown albums. Swift’s Blonde on the Tracks reached right up to Rough and Rowdy Ways, including “I Contain Multitudes” alongside a devasting account of “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” from Blonde on Blonde (1966). Hynde and Pretenders guitarist James Walbourne circulated Standing in the Doorway as nine revelatory installments of a Dylan Lockdown Series, and for her, too, the adventure originated in Rough and Rowdy Ways. “Listening to that song”—she recounted of “Murder Most Foul” during an interview with Tina Benitez-Eves—“completely changed everything for me. I was lifted out of this morose mood that I’d been in. I remember where I was sitting the day that Kennedy was shot, every reference in the song. I called James and said, ‘Let’s do some Dylan covers,’ and that’s what started this whole thing.”

__________________________________

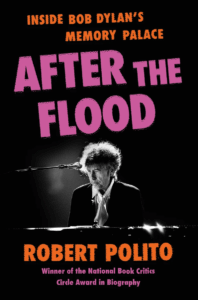

Excerpted from After the Flood: Inside Bob Dylan’s Memory Palace by Robert Polito. Copyright © 2026 by Robert Polito. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.